PREFACE:

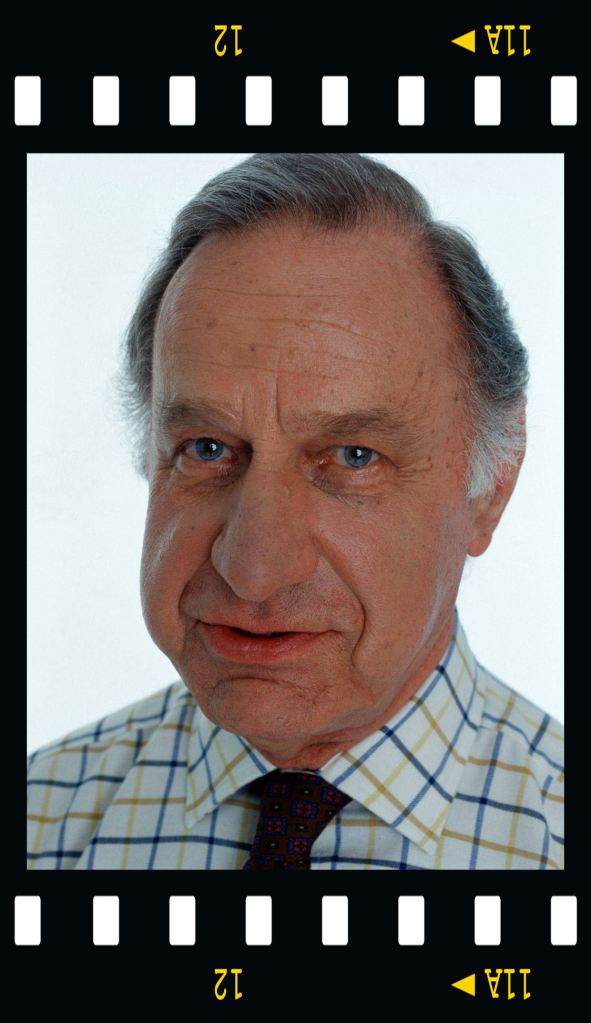

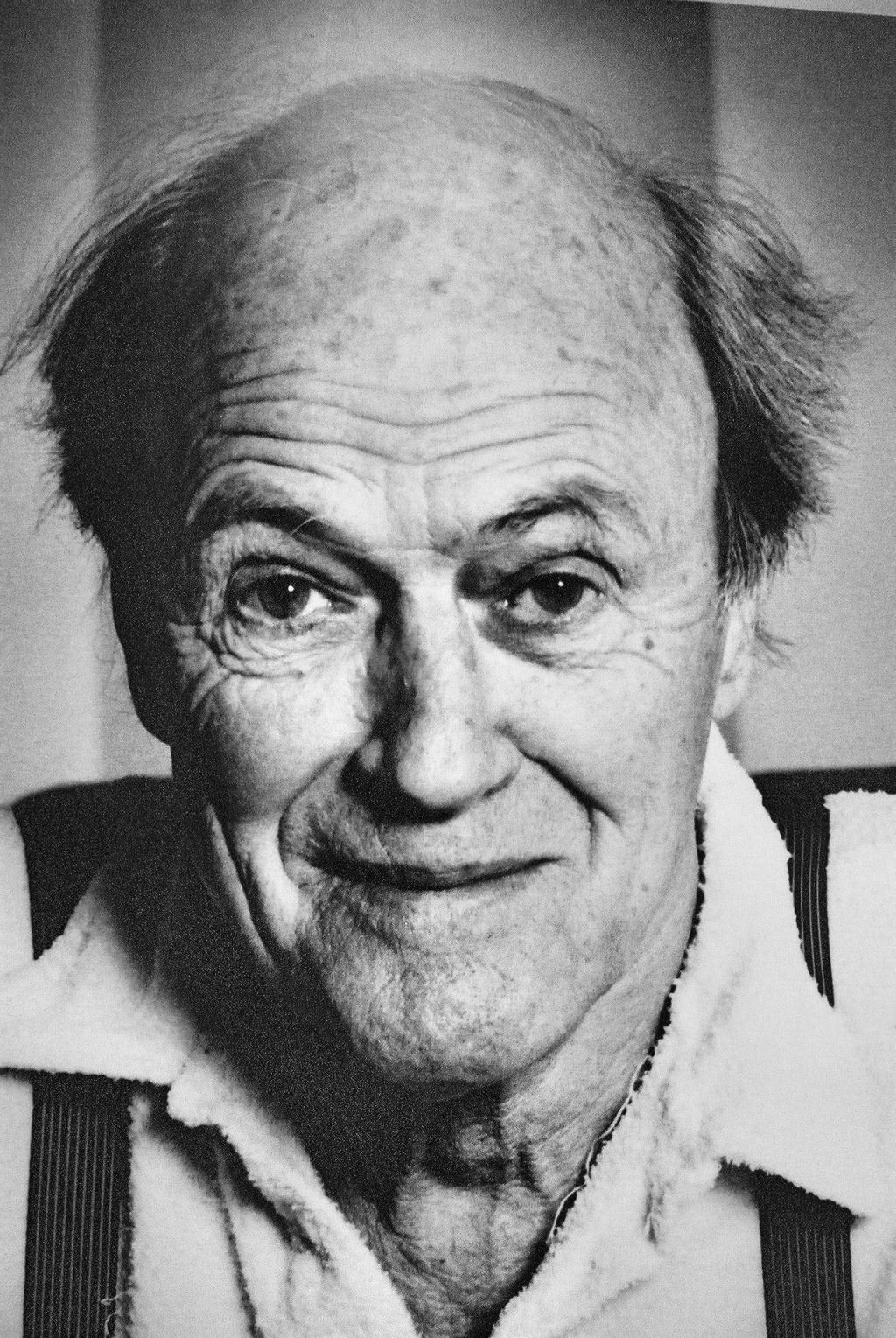

I wrote the following piece about Geoffrey in 2005 for Countryside Books in Newbury after he received his OBE It was part of a series about county heroes – chosen in this case by the author – me – so totally biased! He was kind enough to refer to it as his C.V. It was hardly that, but it was written with love and affection for such a genuine man with a wicked twinkle – We met many times, had many chuckles.

When news of his passing broke on November 5th 2020, it was so very very sad. There was also a very strange serendipity moment for me personally. That same day before the news broke I had been sorting out some books and a card fell out. It was one of Geoffrey’s – he had a penchant for writing on a personalised post card which he placed in an envelope to keep the contents private. Always hand written with his fountain pen and a joy to receive. None were ever dated.

This one said in response to some earlier chats we had had; ‘no great excitement in my life. Very little work, not that that’s a bad thing at my age, still fishing and getting to a lot of home games with my son to see Arsenal. See you somewhere soon no doubt! Hope all is well with you and yours, best wishes G.’

Well, could be better Geoffrey, could be better! God bless and what a privilege to have known you.

‘If there’s a gentle smile….that’s the nicest thing.’

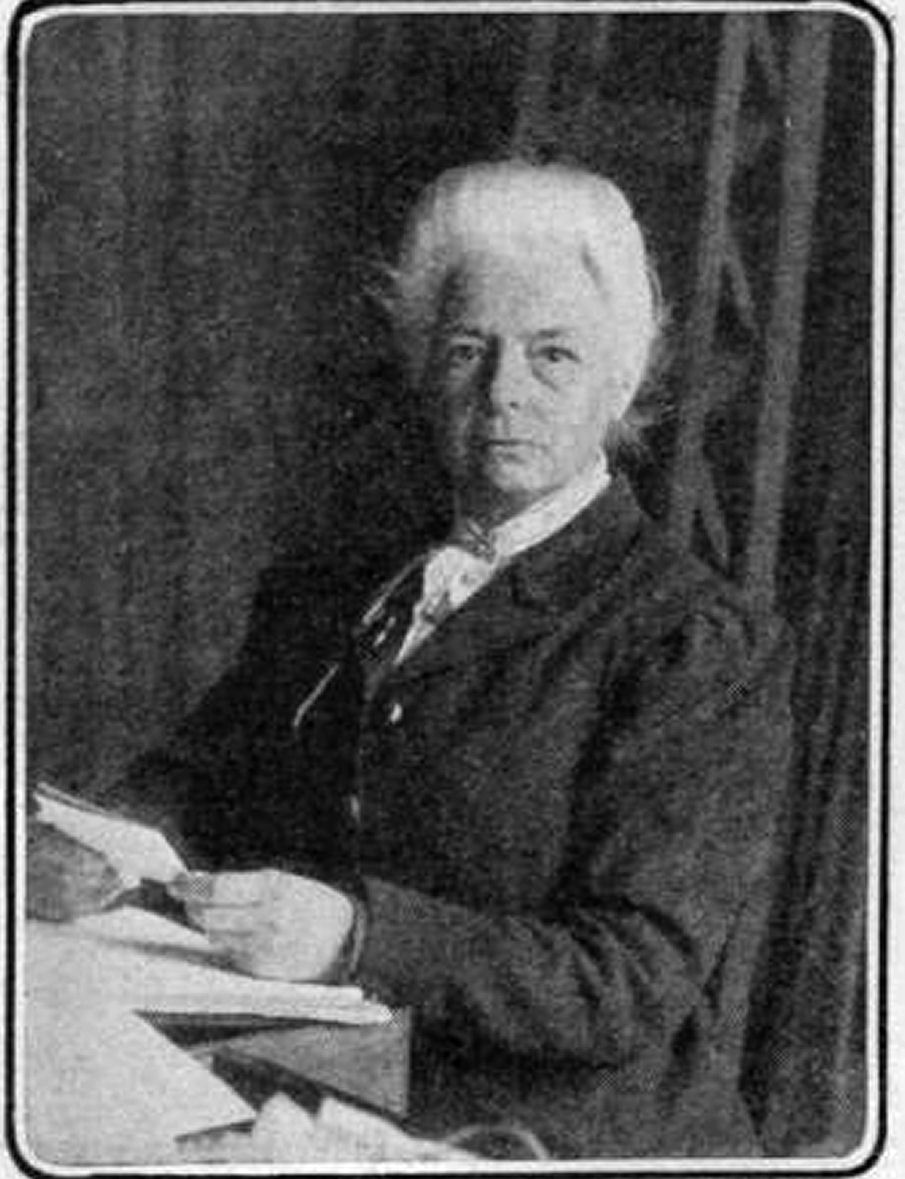

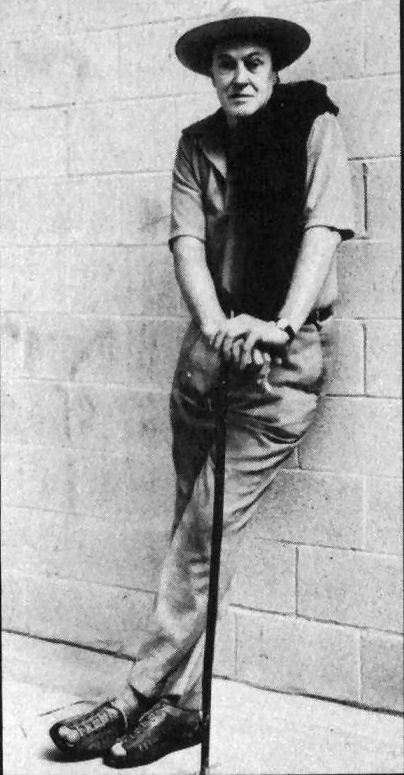

Many ‘gentle smiles’ are directed towards our final county hero.

Smiles associated with pleasure and good memories. The constant flickers of recognition that Geoffrey Palmer encounters exude a warmth of, ‘here is someone I know, someone I like. ‘

Of course, if you are in the public eye, if you are a well-known professional actor, such recognition comes with the territory, but in Geoffrey’s case he carved himself a unique international persona as well as a special local relationship with Buckinghamshire and the Great Missenden area where he lived for the last forty-three years.

The magic of Roald Dahl’s stories and rhymes that began our tour of county heroes now come full circle when we encounter the additional ingredients of Geoffrey Palmer’s voice, and acting skills as he brings the BFG and so many other tales, stories and plays to audio life. This is the other powerful and highly recognisable quality that he holds and uses to perfection – his voice. Flickers of recognition occur in exactly the same way on hearing his warm, controlled, perfectly pitched tones that guide us through the television world of Grumpy Old Men or famously lending his articulate, clipped British tones to the German language to inform us about Audi cars and “Vorsprung durch Technik.”

Geoffrey Palmer is a comfortable presence in so many people’s lives. For many he is, and will always be, Lionel Hardcastle romancing Jean (Judi Dench) in As Time Goes By. For others he’ll always be Ben Parkinson, father to Russell and Adam and husband to Ria (Wendy Craig – ‘Butterflies.’) . Yet others recall the hapless Jimmy, brother-in-law to Reginald Perrin (Leonard Rossiter – The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin

Or, like me, do you miss the batty Major Harry Kitchener Wellington Truscott (Fairly Secret Army) or perhaps look forward to meeting Admiral Roebuck again as he and ‘M’ (Judi Dench) deal with a belligerent James Bond (Tomorrow Never Dies).? A very long list indeed is possible here but before such a list of credited performances began its genesis, Geoffrey Palmer’s own entry to the world was on June 4th 1927 in North Finchley, a companion for his three-year old brother.

As you explore Geoffrey’s early life with him, it becomes clear that he was keen on following a military career of some kind. At Highgate School he ended up as Captain of Shooting, claiming it was the only thing he was good at unless you count the award of a ‘really naff dictionary of quotations for “the reading in chapel prize.”‘

As a teenager he aspired to what he regarded as the glamour of the Fleet Air Arm but at the medical discovered he was marginally colour blind so that avenue was closed off. In the event, by 1946, he had opted for the Marines as an HO (Hostilities Only) recruit, reporting to 928 Squad at Deal. He looks back on this time, not with misplaced nostalgia, but with a real affection that not only did he enjoy being a Royal Marine, he was also quite good at it. Indeed, his talent for shooting, which had won him accolades at school, came into its own as he undertook a small arms instructor course and eventually was promoted to full Corporal Instructor

In 1948, as an NCO, he left the Service, receiving a special grant given to ex-servicemen for re-training in ‘Civvy Street.’ In Geoffrey’s case this involved something to do with Dutch baked beans and Swedish salad cream in an import-export business but more importantly he confided, ‘I just spent the time looking at the girls and thinking, “Oh gosh, I wish I were brave enough to ask them out.”‘

This ex-corporal instructor, now trainee business man, but hopelessly shy when it came to dating, was still living with his parents in North Finchly. He did break through his shyness enough to have a girlfriend and it is to her that credit must go for introducing Geoffrey Palmer to the acting profession he was to make so much his own.

While he enjoyed the world of the local Woodside Park Players, his disillusionment with the business world was growing. He recalls, ‘The girlfriend had got me into the local amateur dramatic society around this time and I suddenly thought one day, I really cannot do this bean rubbish anymore. I was twenty-one or twenty-two and had no interest in trying to sell Dutch baked beans and I remember thinking I’d better go and see the personnel manager, Mr. Ritter. So I spoke to his secretary, it was a Friday I remember, and I said I’d like to see Mr. Ritter. “What’s it about?” she demanded. “Well I think I want to leave,” I said. “I’ll see if he’s free,” and I went in.

“Yes Palmer. What is it?”

“I want to leave sir.”

“What are we paying you?”

“Five pounds a week sir.”

“Suppose we give you seven?”

And I though, “You s**t. If I was worth seven why didn’t you give me seven last year?” I said, “No thank you,” and left.’

He drifted a little, helping an accountant friend but that was not his forte. ‘I couldn’t add up or anything.’ He persevered with the amateur dramatics, discovering to his amazement that some people actually made a living out of being an actor. He also found it was very pleasurable to experience people laughing and clapping at the end of a performance. He was hooked.

So in his early twenties, he placed his foot on the first rung of his theatrical ladder, landing a job with the Q Theatre on the north side of Kew Bridge. The catch was that he was an unpaid trainee assistant manager.

Surviving for around a year he did achieve waged status of about three pounds a week or so before moving to the Grand Theatre, Croydon, as an assistant stage manager. Locating props and playing incidental parts, his theatrical apprenticeship steadily progressed until he was taken into the repertory company as ‘juvenile character.’ He began working in rep, e.g. Leatherhead, Canterbury, Guilford, Aberdeen, Glasgow and Edinburgh, building a reputation by his mid-twenties as a ‘youngish leading man.’

Despite having what Geoffrey told me was a ‘grotty agent,’ it was right time, right place, right age, that worked in Geoffrey’s favour as his theatrical training was ideal for the new doors opening in commercial television around the mid 1950’s.

At this time, Geoffrey was sharing a sparse flat ‘at the wrong end of Chelsea’ close to Granada’s London studios, so picked up lots of bits and pieces with them. He also worked for ATV when they had the Wood Green Empire and the Hackney Empire before they were at Elstree. He worked with some of the top variety shows and comedians of that time such as Arthur Askey, Harry Worth, Dickie Valentine and his own hero, Jimmy James.

Geoffrey’s famous career, yet to be realized, as a voice-over artist, could have been said to have started at that time when he was given ‘out of vision’ announcements:

‘From the North, Granada presents, THE ARMY GAME, starring Michael Medwin, William Hartnell, Alfie Bass, etc. etc. .’

Geoffrey loved working on The Army Game. Apart from the fact that the studio was only five-hundred yards from his flat, and it ran for over four years, Geoffrey fondly recalls, ‘I got seven guineas for nothing – for half a minute’s work every Friday night and then I’d do something for the odd quiz show – I was the local, cheap, jack-of-all-trades.’

What really got him closer to being in front of the television cameras was his job on The Alan Young Show around 1957. Geoffrey explains. ‘Alan Young wasn’t happy the way the show was shot when they did the first one – so he wanted someone (this was live television as well) to act his part in the dress rehearsal of the two main sketches – brilliantly funny sketches – that made up the show. He wanted someone to do what he did on camera so he could see if the camera shots were right and decide what he thought should be a close up. So that was my job. I did what he did on the rehearsal and then I was finished. But again, being around, I did the ‘out of vision’ announcement, “From the North, Granada, it’s The Alan Young Show, starring Alan Young, Petula Clark our guest star this week,” (or Pearl Carr and Teddy Johnson) or whoever it was. It wasn’t because I had a wonderful voice. I just happened to be there.’

Sorry Geoffrey – the voice cannot be discounted so easily. His television commercial work has become legendary. The pitch, the diction, shading and richness of his voice, honed by thousands of hours of acting was excellent then and remained first class throughout that professional strand of his long career. Way back in 1984, the Audi car advertisement is something still associated with him.

‘A German lady who lived opposite,’ recalled Geoffrey, ‘said it was a pity that everyone talked about that commercial. “This is very silly,” she said, “because Geoffrey does not pronounce it correctly,” totally missing the point!’

Geoffrey’s theatrical career and television work continued apace during the 1960’s when he was wining parts in some of the legendary series of that decade: Police Surgeon; The Avengers; The Saint; Top Secret; Out Of The Unknown; Z-Cars; Paul Temple; Dr. Who: and many many more were collected along the way. However one series in particular had another significance for him.

It was a series for Granada called Family Solicitor, and it was , while staying in digs, he met the woman he was to fall in love with. Still a shy, quiet man, he pluck up the courage to propose to and marry Sally Green in 1963. That same autumn, they moved to Buckinghamshire, the county they have loved and lived in for over forty-three years.

Geoffrey continued to become more and more sought after for television work – his face now very recognizable, even if the name was still one yet to be more firmly established in people’s minds. His work in the 1970’s however, soon put that right. In 1971, John Osborne cast him in his play West Of Suez at The Royal Court Theatre and Lindsay Anderson grabbed him for a key role as the doctor in his hit film O Lucky Man (1973). But for Geoffrey, it was a telephone call to his Buckinghamshire home in 1974, that really confirmed he had arrived.

The call was from Sir Laurence Olivier who offered him a part in his National Theatre production of J.B. Priestly’s play Eden End. He did not audition him as he knew he wanted Geoffrey Palmer to play Priestly’s Geoffrey Farrant in this plot of family undercurrents, which he did to great acclaim. Other substantial parts with legendary actors were on the cards, so whatever else he went on to achieve he ended up not only working for Sir Laurence Olivier, but with, and for, Sir John Gielgud, Paul Scofield and Sir Ralph Richardson. ‘Not a bad bunch to work with, is it?’ he said to me.

The fame that was to come his way, though, did not rest in his highly regarded theatrical performances, but as one of television’s favourite sit-com stars. This began in the mid 1970’s with The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, and the role of Jimmy. However, it may never had been, as Geoffrey explained to me, ‘John Howard Davies directed the pilot – the first one they did – and the pilot worked so then they commissioned a whole series, but Jimmy didn’t appear in the first one and I did not know Howard Davies. So if Jimmy had appeared in the pilot, someone else would have got the job. Then my career would have been very, very different.’

Geoffrey knew Gareth Gwenlan who directed the series, as he had previously worked on some pilots with him written by Carla Lane and by Michael Frayn. After the first series of Fall and Rise, Gareth came down to Geoffrey’s Buckinghamshire home with another Carla Lane script to show him and that was Butterflies.’ So it is very much a toss of the coin’, he told me.

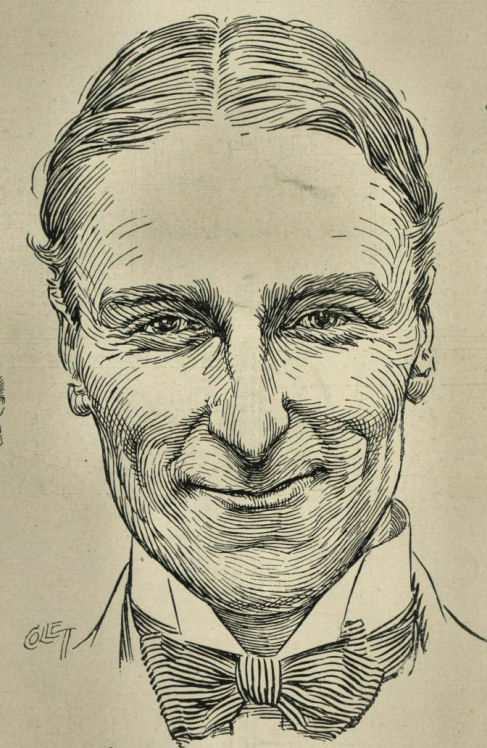

I have refrained (until now) from mentioning what have become almost obligatory and usually first line introductory descriptions of Geoffrey’s face. It is very personal to refer to someone as lugubrious, to refer to their hangdog countenance or blood-hound looks, or see see them as having an archetypal middle-class, possibly slightly dull, down-trodden husband expression (whatever that may be). Sue Lawley began a Desert Island Discs radio programme with the words, ‘His mournful expression and rich voice have made him a household name.’

These descriptions and many more abound, not with the taint of insult but affection, and, as his sit-com fame increased, so did the ways of describing him. When we spoke of this, he did seem to have sneaking preferences for one piece that began, ‘The rugged, craggy face that has often dominated our television screens in recent years.’

Can you be rugged, craggy and lugubrious? I’m not sure but in the final analysis, he has an actor’s face – one of expression and interest that holds the viewers, theatre audiences and film-goers alike. He has a voice that similarly compels listening attention and a superb acting talent that sees him range from Trollope to Shakespeare to Dickens and Priestly on the one hand, and to John Cleese, Carla Lane, David Nobbs and Bob Larbey on the other. It was no surprise, except to Geoffrey, that his ‘Services to the Theatre’ were rewarded in the 2005 honours list with an OBE.

His role as Lionel Hardcastl, romancing Jean in As Time Goes By has scored quite an astounding following. In some cases, as in America, this is their first introduction to Geoffrey Palmer, British actor. For American ladies of a certain age who fantasize about being Judy Dench’s Jean, they have dedicated websites and even meet up for ‘Lionel Hardcastle Lunches.’

Of course Lionel is never there but imagine the scene should one Geoffrey Palmer happen to call by! Geoffrey is more realistic about As Time Goes By. ‘You would think it was a Bertrand Russell or something the way people talk about it – I know it is not. I think it is a very clever situation comedy – end of story. That’s all there is.’

Geoffrey’s celebrity status does not sit easily on his shoulders as one might imagine. For him, his job happens to be that of an actor, albeit now a very successful and well-known one who is very much a part of the Buckinghamshire scene – a local celebrity of course, but the label is not of his choice, it just comes with the territory. Had he not been Geoffrey Palmer, actor, he quite fancied his hand at farming – not so many ‘gentle smiles’ in farming and probably not so many requests to support good causes and turn up at local events – something he does with a refreshing frankness. Commenting on a recent charity wristband campaign for the local Iain Rennie Hospice at Home, for which he is patron, he explained to me,’If they want publicity, the’ve got a better chance of doing it if they have a quasi-celeb. otherwise the Bucks Free Press, or the Gazette or the Herald won’t turn up at all. I don’t do much.’

Geoffrey does have a friendly, accessible character that endears him to his local community, and it is the same accessibility he would extend to anyone whom he felt he could assist: a willingness to turn up and be Geoffrey Palmer – we might see Lionel, Jimmy or Ben – that’s up to us – and bring publicity and attention to the cause in hand.

He doesn’t do much – he’s just Geoffrey Palmer, OBE, actor and Buckinghamshire Hero

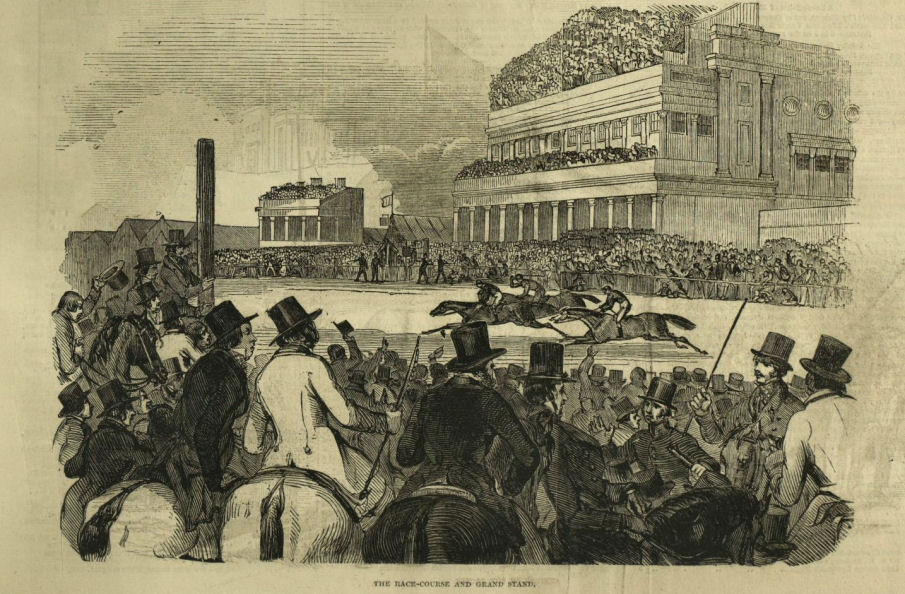

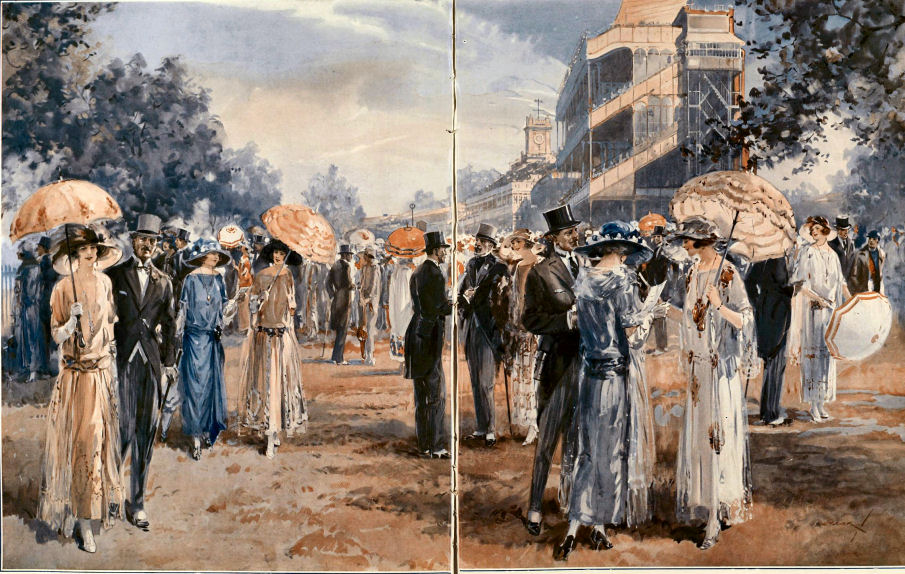

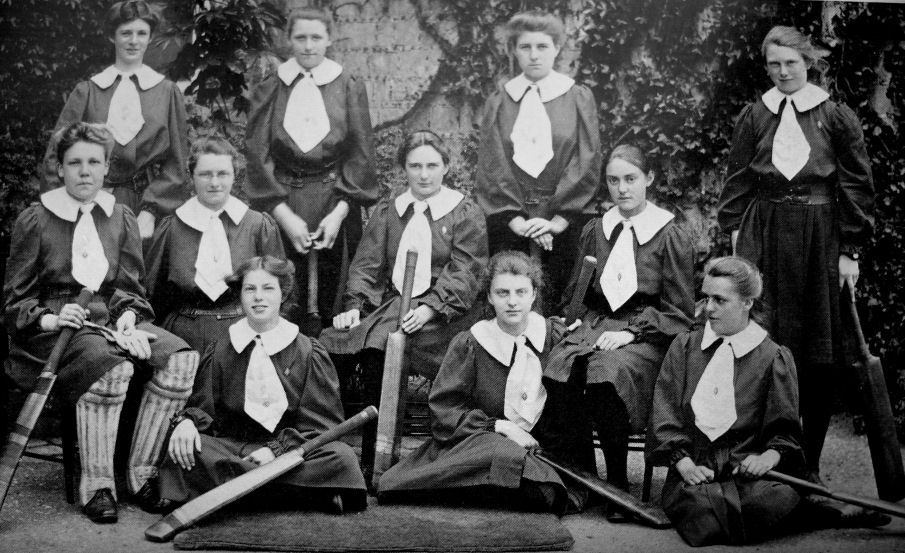

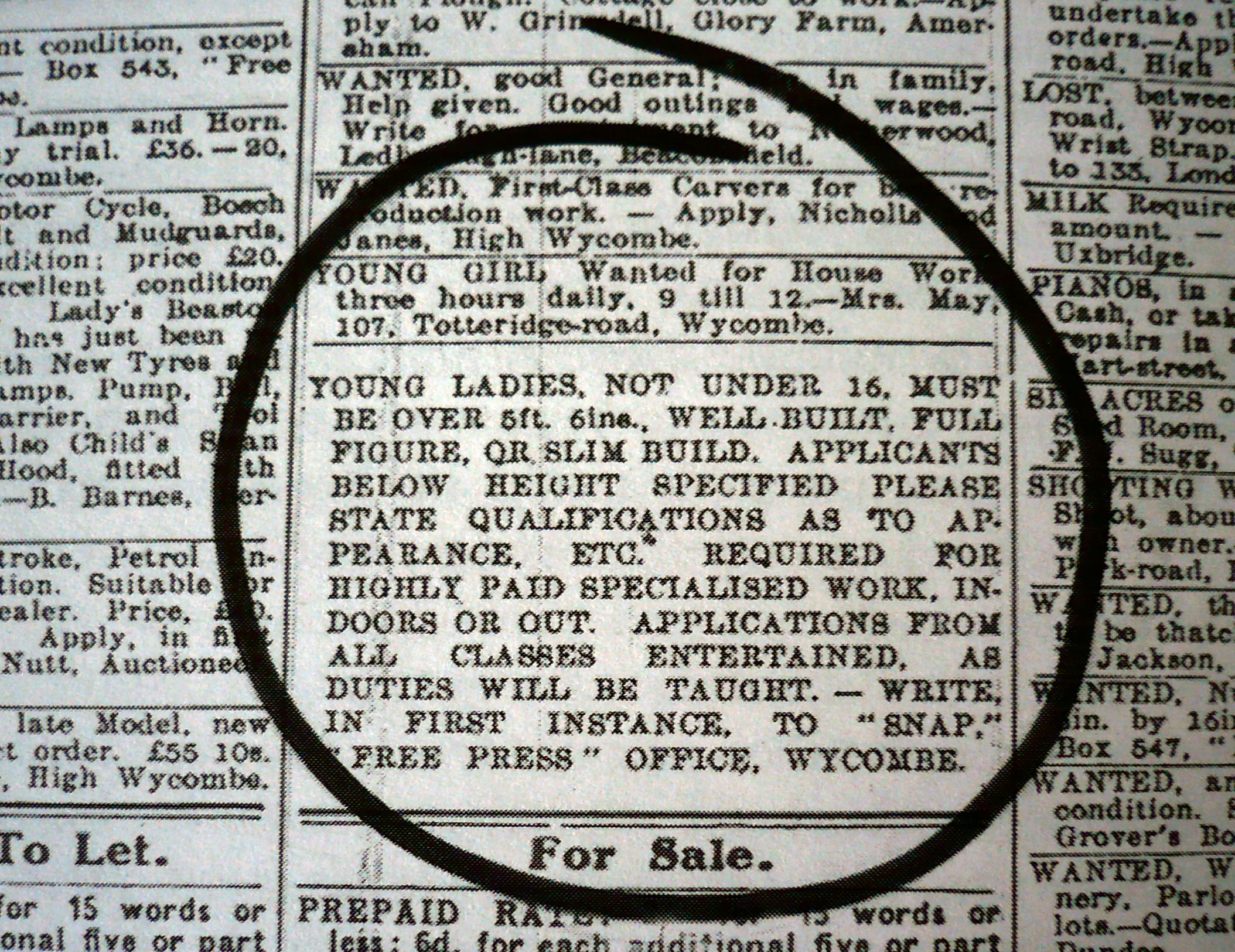

1910-1920?

1910-1920?

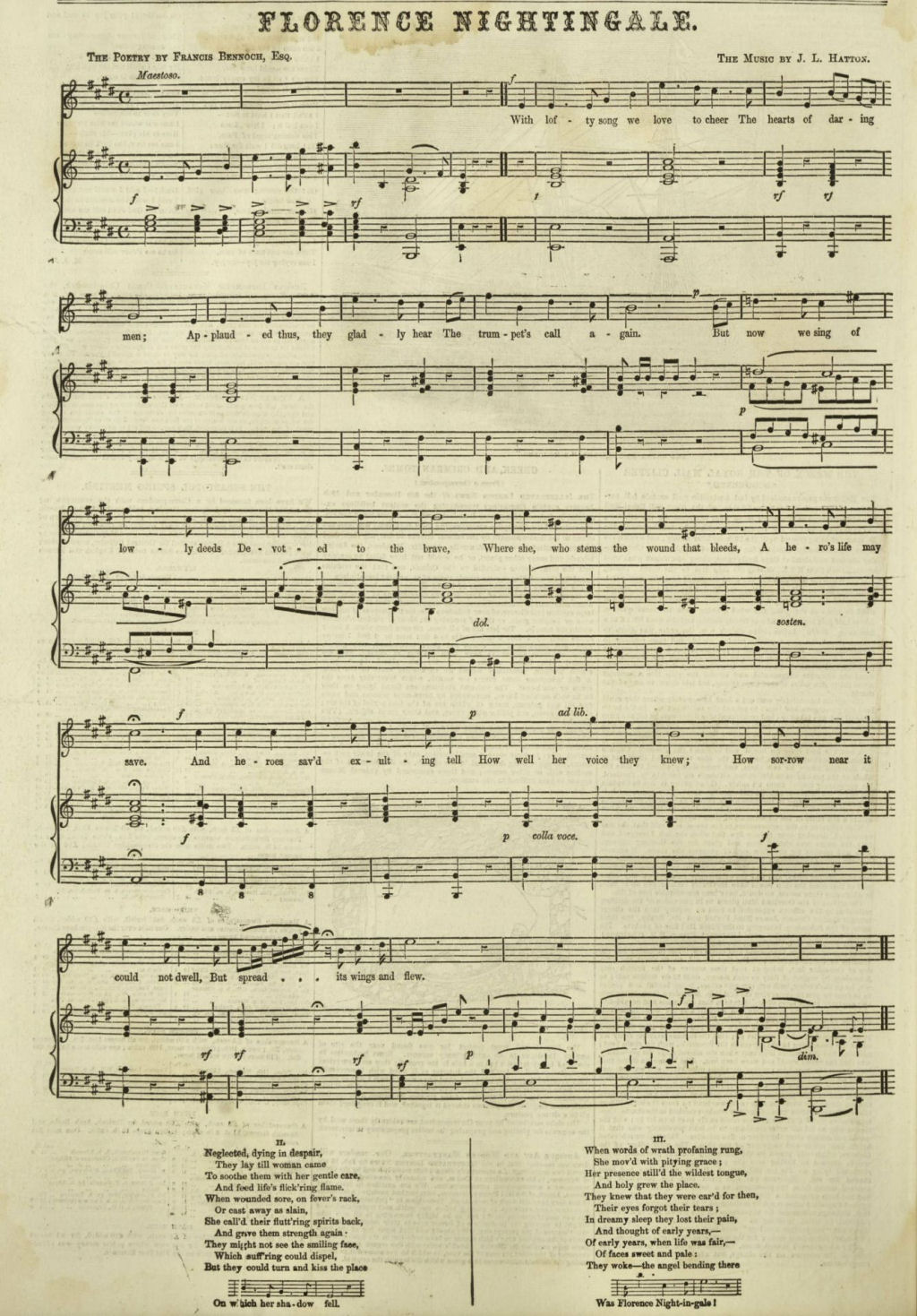

However, her nursing work in Crimea was only to be a tiny part of a career spanning over half a century. Crimea was her catalyst, the springboard, as some observers have called it – to transform not only the lowly image of the British soldier, but the disreputable public perception of nursing.

However, her nursing work in Crimea was only to be a tiny part of a career spanning over half a century. Crimea was her catalyst, the springboard, as some observers have called it – to transform not only the lowly image of the British soldier, but the disreputable public perception of nursing.

©SPUDGUN67

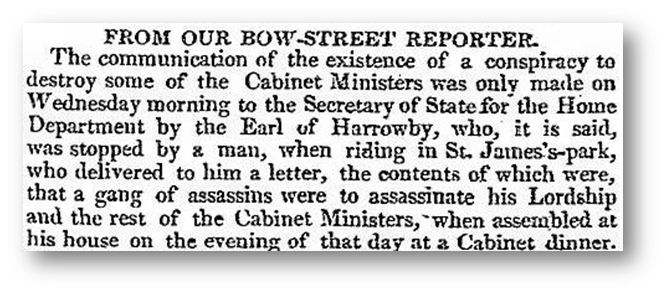

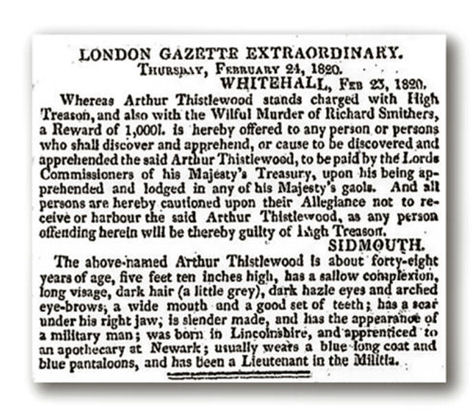

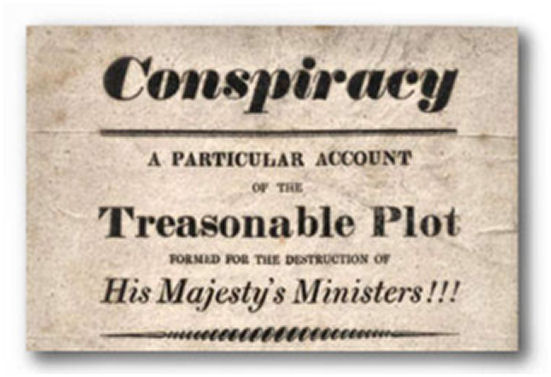

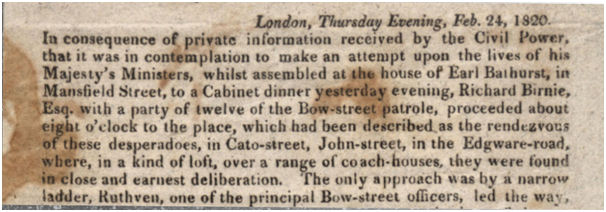

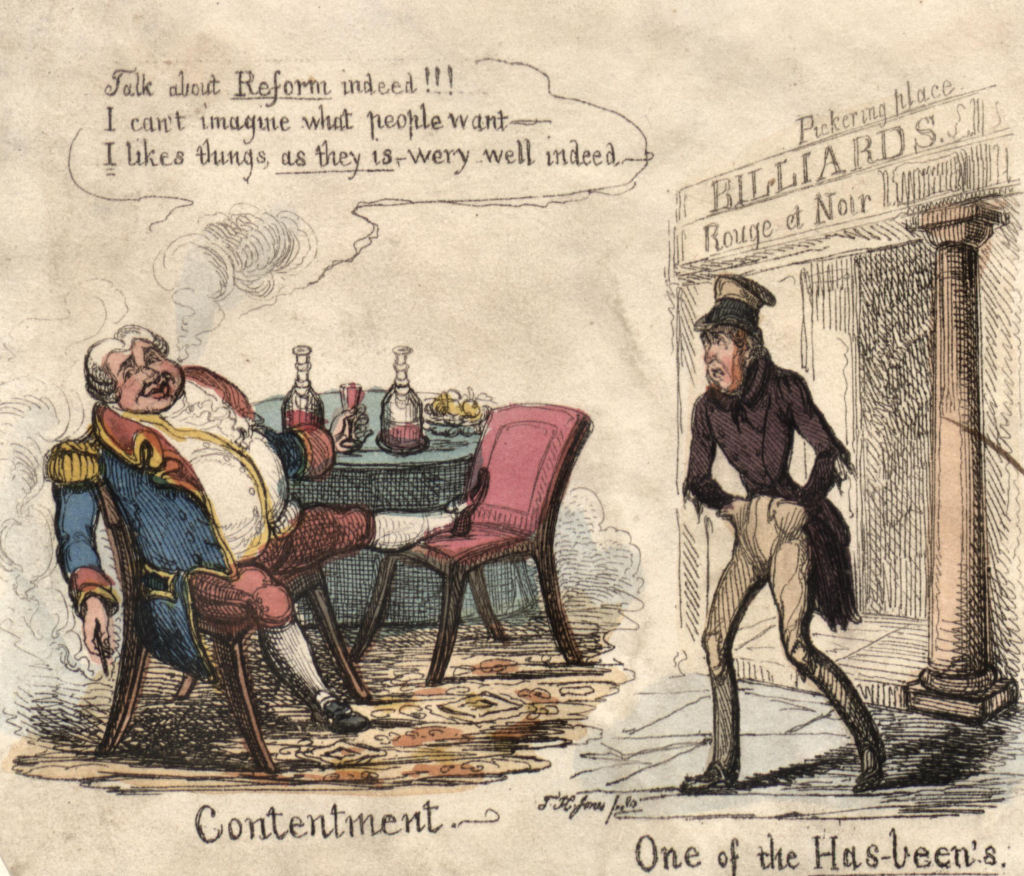

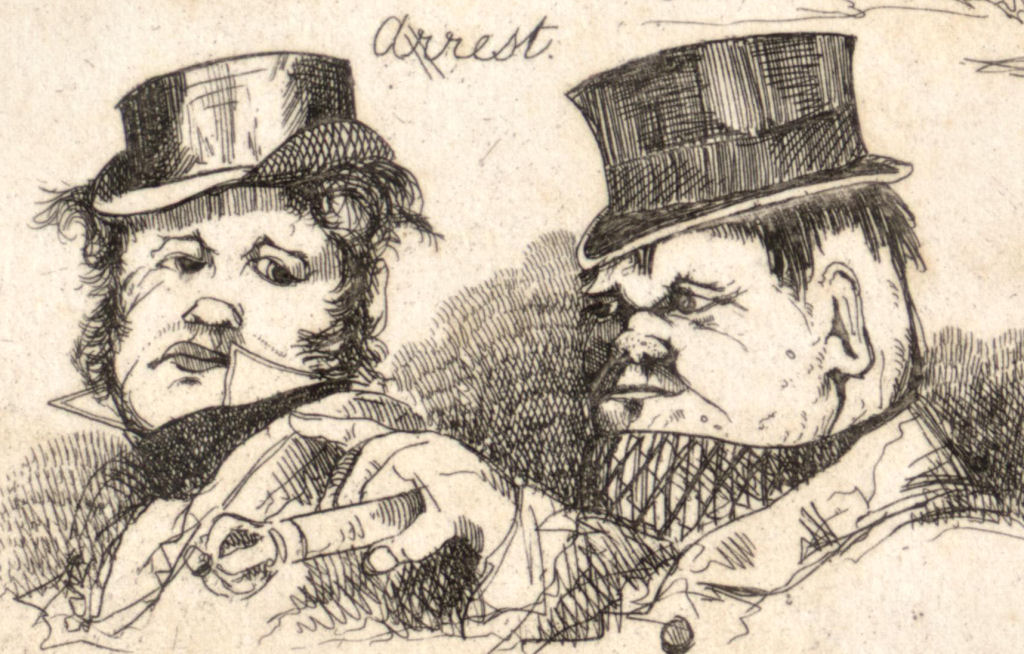

©SPUDGUN67 ‘From Our Bow-Street Reporter,’ The Times (London: England) 25 Feb 1820:3

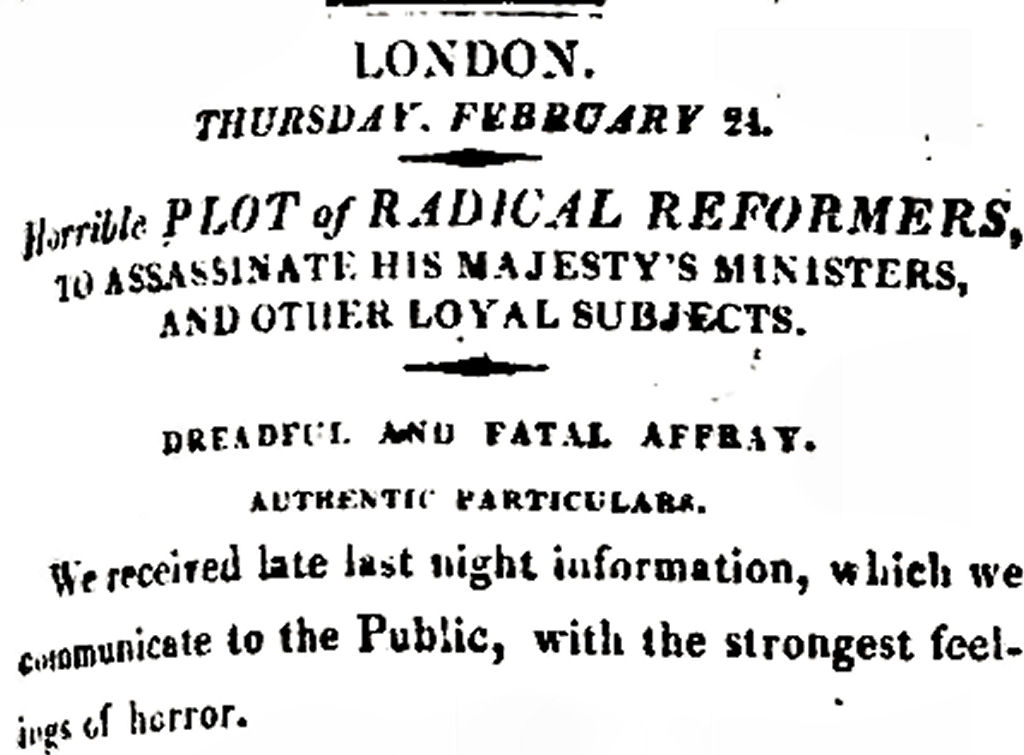

‘From Our Bow-Street Reporter,’ The Times (London: England) 25 Feb 1820:3 The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England on Monday 16 August 1819 when cavalry charged into a crowd of 60,000–80,000 who had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation.

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England on Monday 16 August 1819 when cavalry charged into a crowd of 60,000–80,000 who had gathered to demand the reform of parliamentary representation.

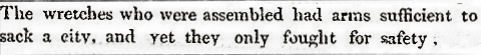

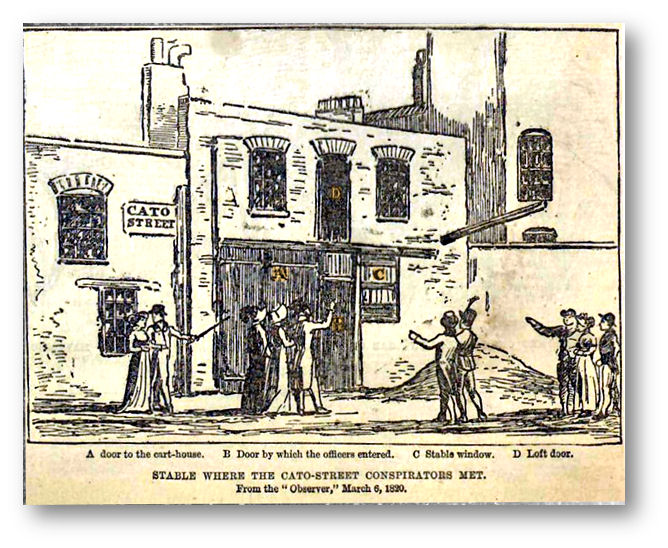

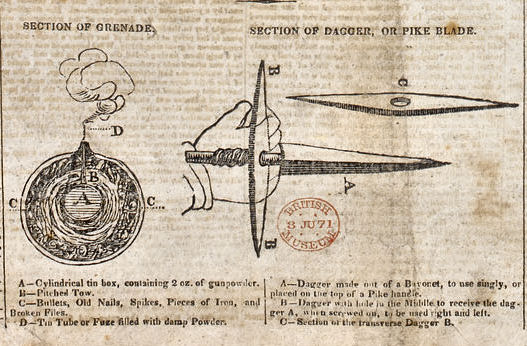

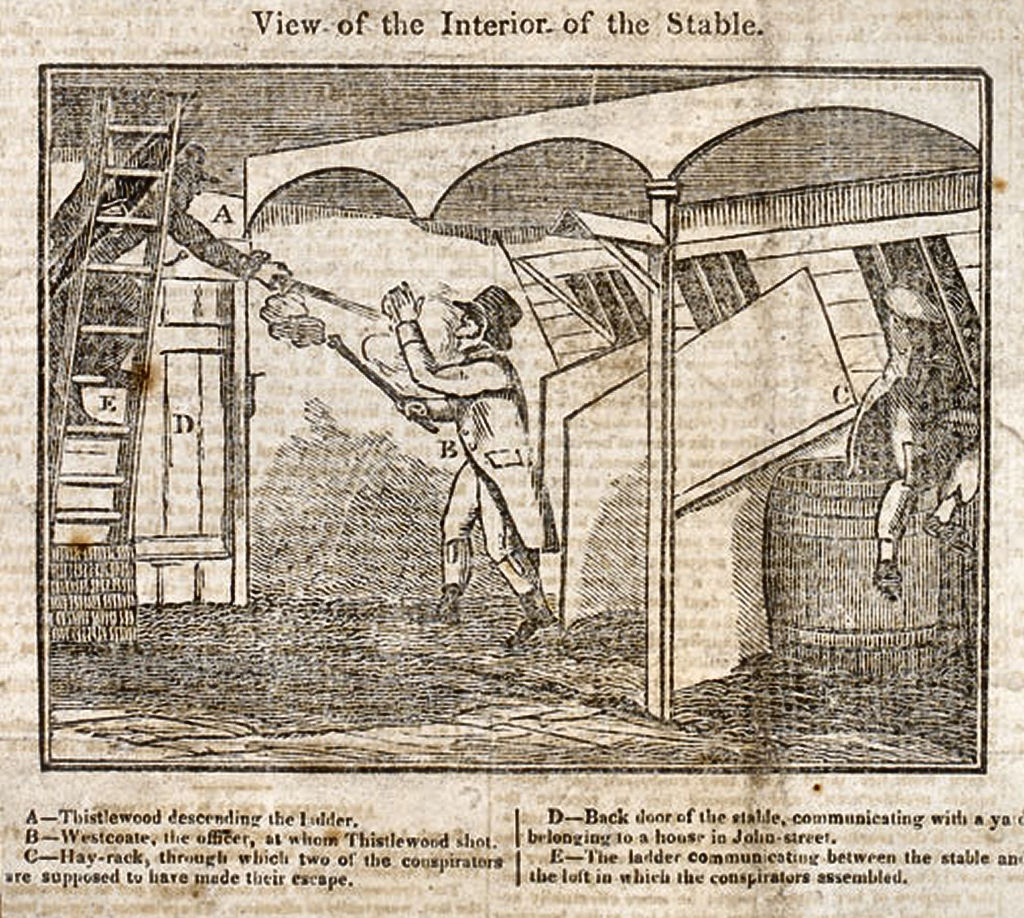

Source: The Times Editorial (London, England), Tuesday, Feb 29, 1820; pg. 2; (the conspirators rented stable premises in Cato-street, Edgware in London)

Source: The Times Editorial (London, England), Tuesday, Feb 29, 1820; pg. 2; (the conspirators rented stable premises in Cato-street, Edgware in London)

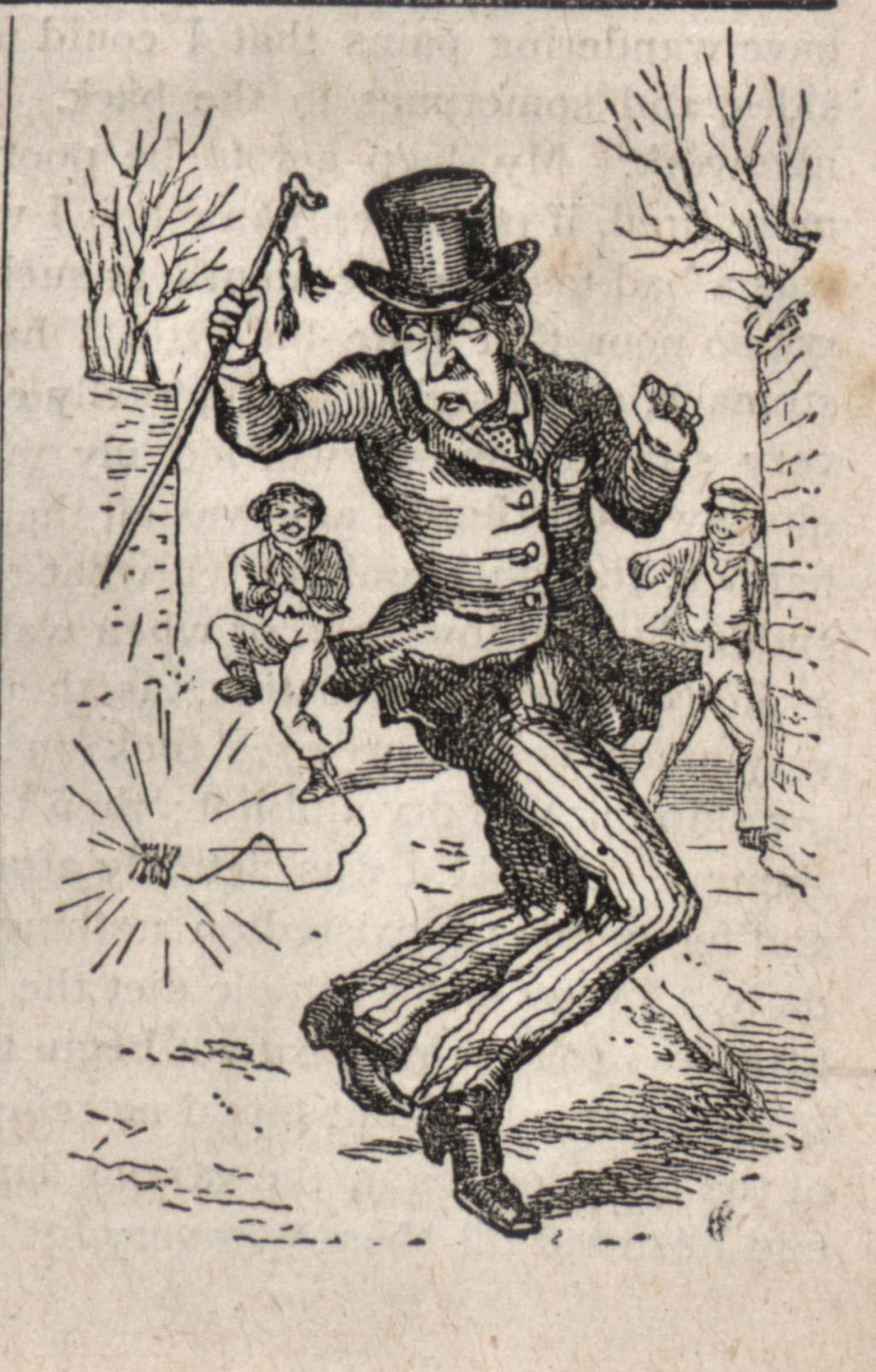

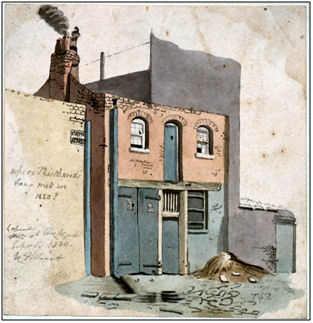

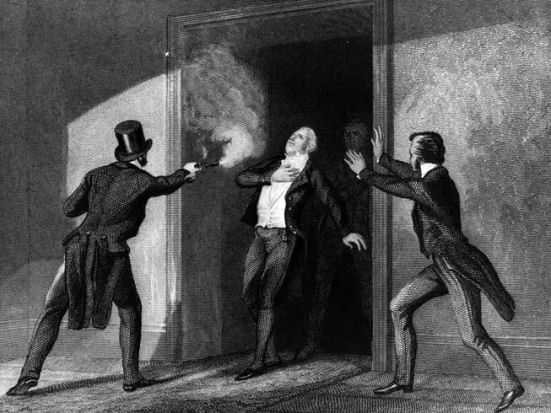

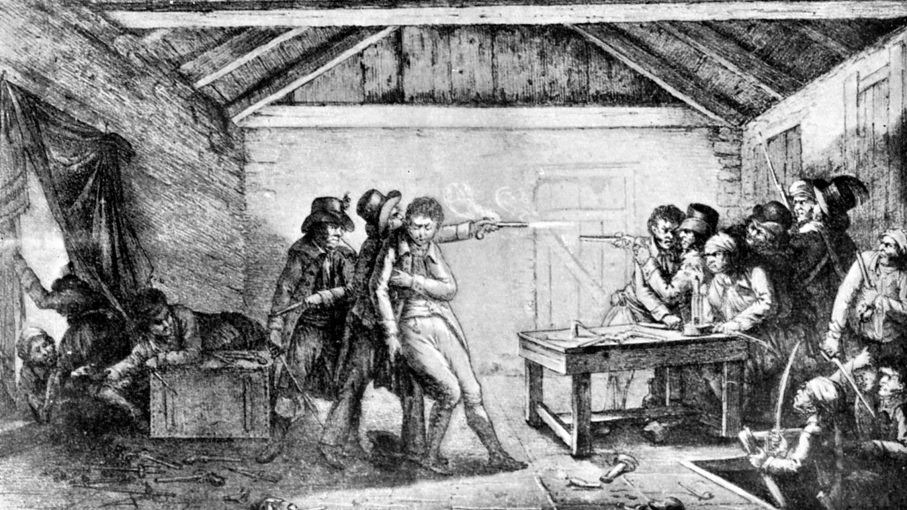

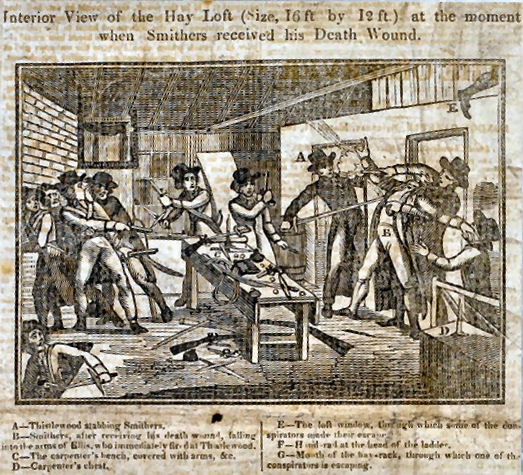

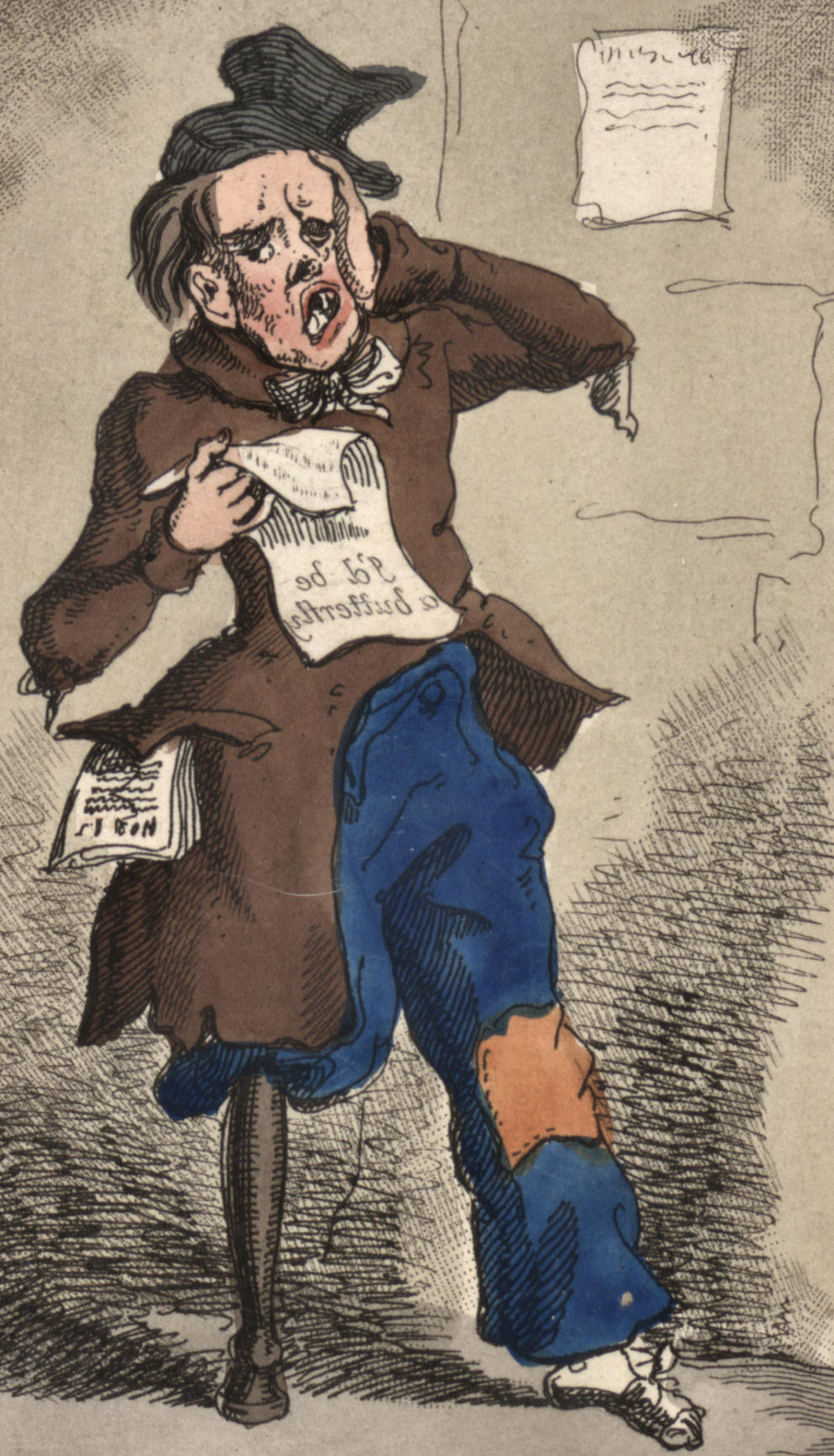

Drawing of Arthur Thistlewood depicting his wilful murder of Richard Smithers, police officer on the evening of February 23rd 1820 in the stable-loft in Cato-street, Edgware.

Drawing of Arthur Thistlewood depicting his wilful murder of Richard Smithers, police officer on the evening of February 23rd 1820 in the stable-loft in Cato-street, Edgware.

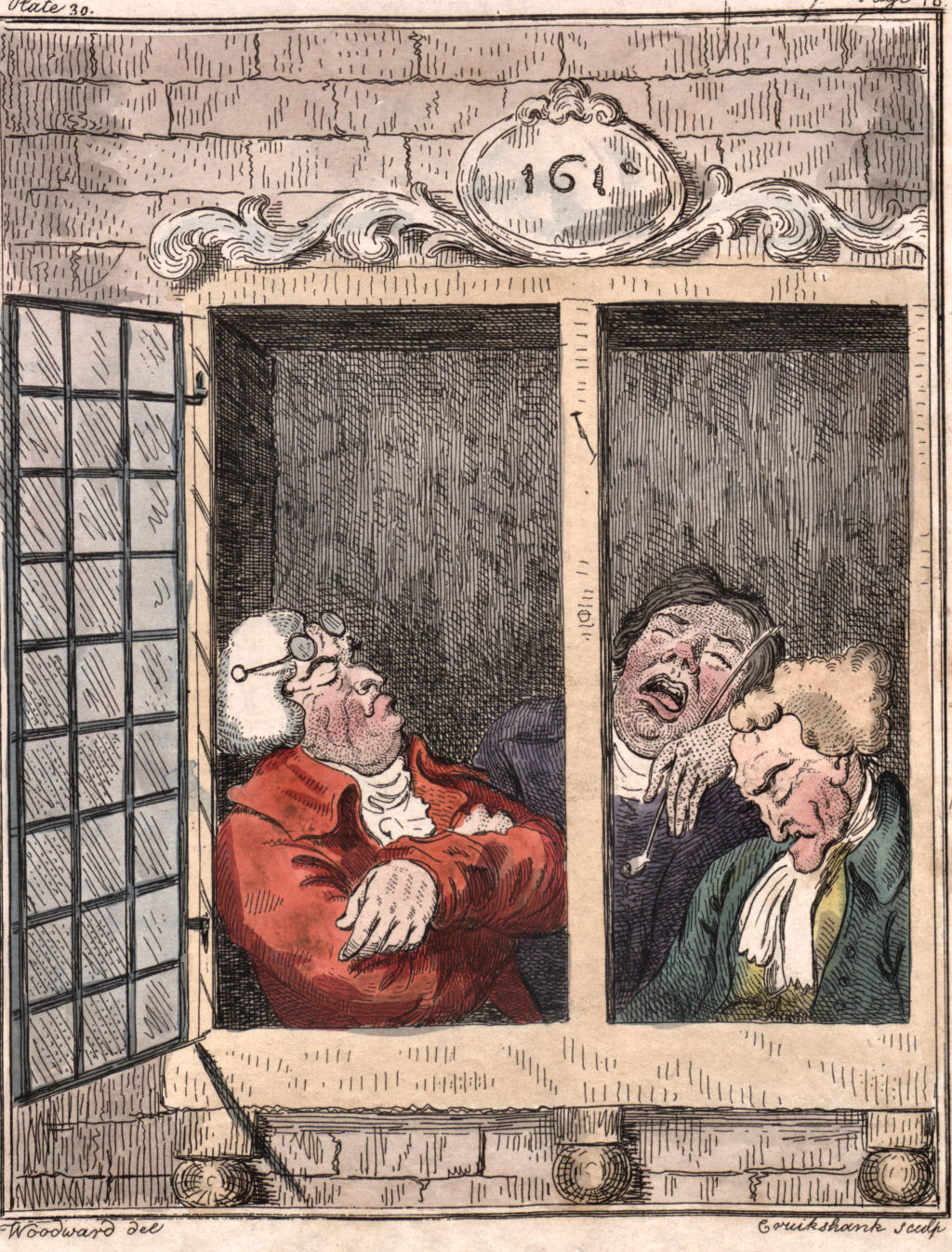

Bow Street Police Court

Bow Street Police Court

The first stone rebounded off the wall, just missing the window.

The first stone rebounded off the wall, just missing the window.

Theories of swarthy foreigners, ogres and villainous plots were starting to collapse all around. Here was a real mystery: why on earth would such a wretched old man, hindered from escape by a wooden leg, commit such a serious crime?

Theories of swarthy foreigners, ogres and villainous plots were starting to collapse all around. Here was a real mystery: why on earth would such a wretched old man, hindered from escape by a wooden leg, commit such a serious crime?

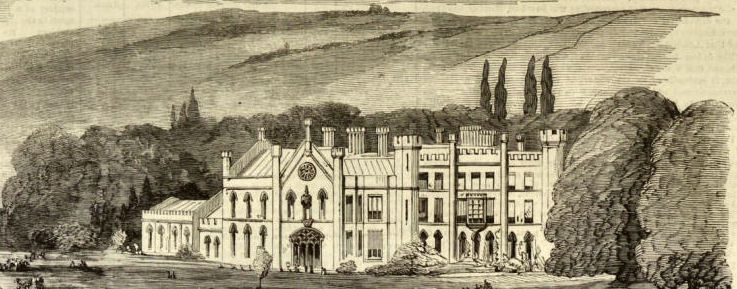

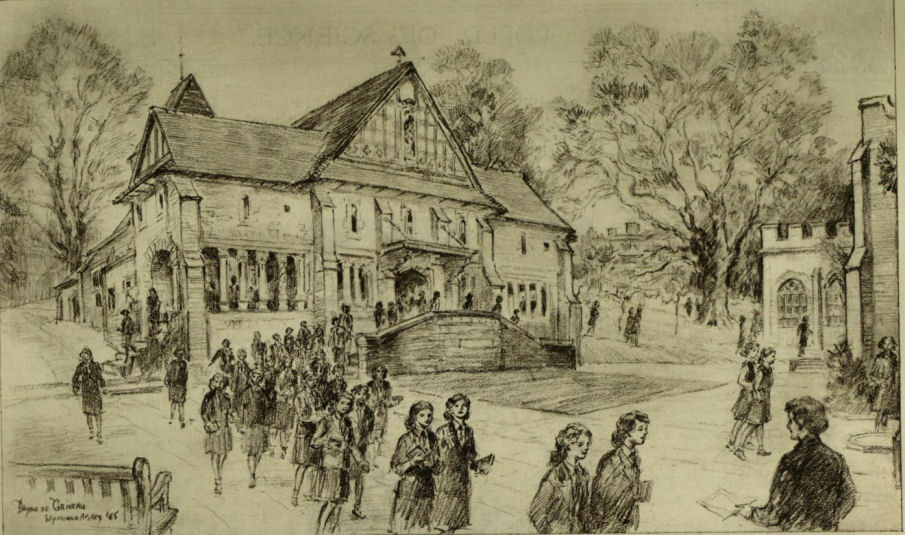

‘Stands there a school in the midst of the Chilterns

‘Stands there a school in the midst of the Chilterns

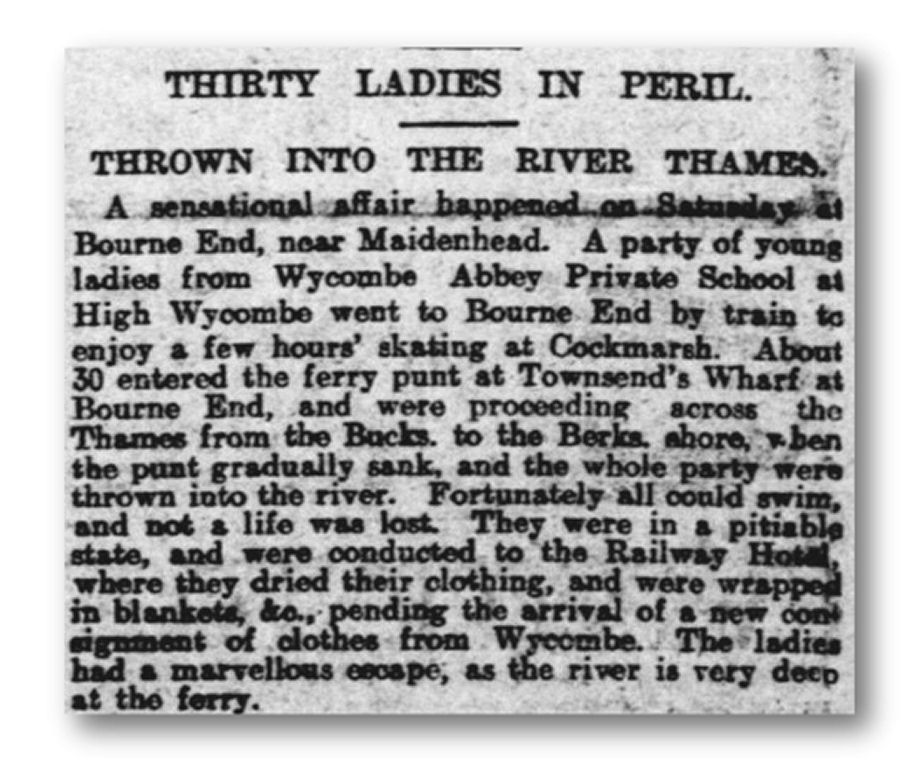

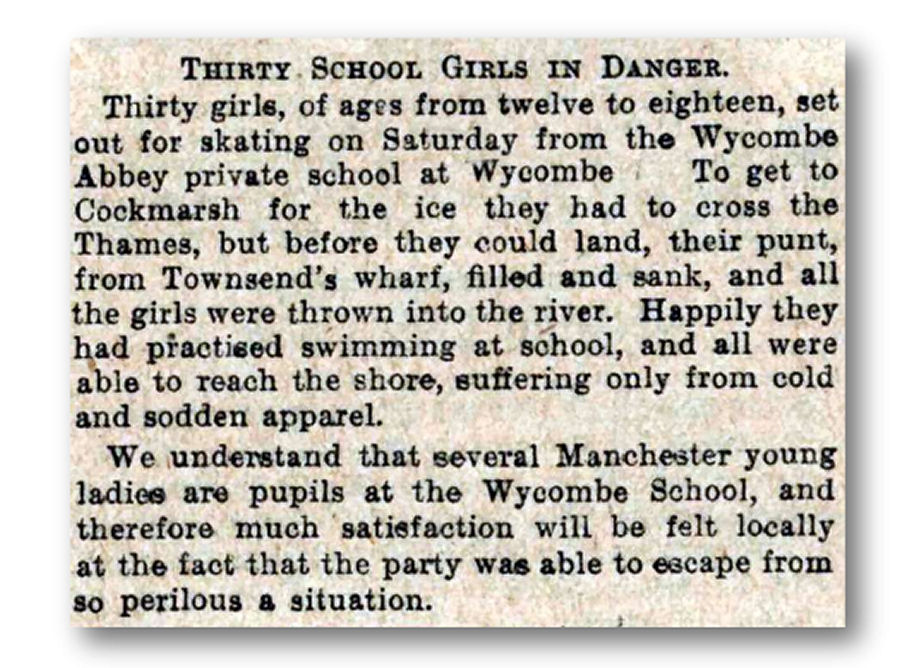

She also allowed a great deal of fun to be had at the school: “Let us have games of all kinds, lawn tennis, fives, bowls, croquet, quoits, golf, swimming, skating, archery, tobogganing, basketball, rounders and hailes,’ she wrote.

She also allowed a great deal of fun to be had at the school: “Let us have games of all kinds, lawn tennis, fives, bowls, croquet, quoits, golf, swimming, skating, archery, tobogganing, basketball, rounders and hailes,’ she wrote.

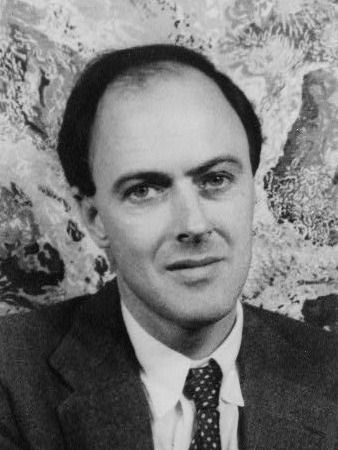

This one priceless example contains many of the traits of the adult Roald Dahl we are about to uncover: inventive intellect, doing something no one else has done, practical joking, perceptive timing, risk taking and bombing.

This one priceless example contains many of the traits of the adult Roald Dahl we are about to uncover: inventive intellect, doing something no one else has done, practical joking, perceptive timing, risk taking and bombing.

Rest in Peace – Roald Dahl, 1916-1990

Rest in Peace – Roald Dahl, 1916-1990 This blog is very specific in its intentions to reinforce (once again) that nothing is new in this world, merely re-arranged.

This blog is very specific in its intentions to reinforce (once again) that nothing is new in this world, merely re-arranged. [

[

The Prisoner has threatened to be even with the Watch; but he did not say which one of them; therefore I hope the Watch will be protected. When I knocked the Prisoner down, he reeled six Yards before he fell, and then said I had killed him.

The Prisoner has threatened to be even with the Watch; but he did not say which one of them; therefore I hope the Watch will be protected. When I knocked the Prisoner down, he reeled six Yards before he fell, and then said I had killed him.

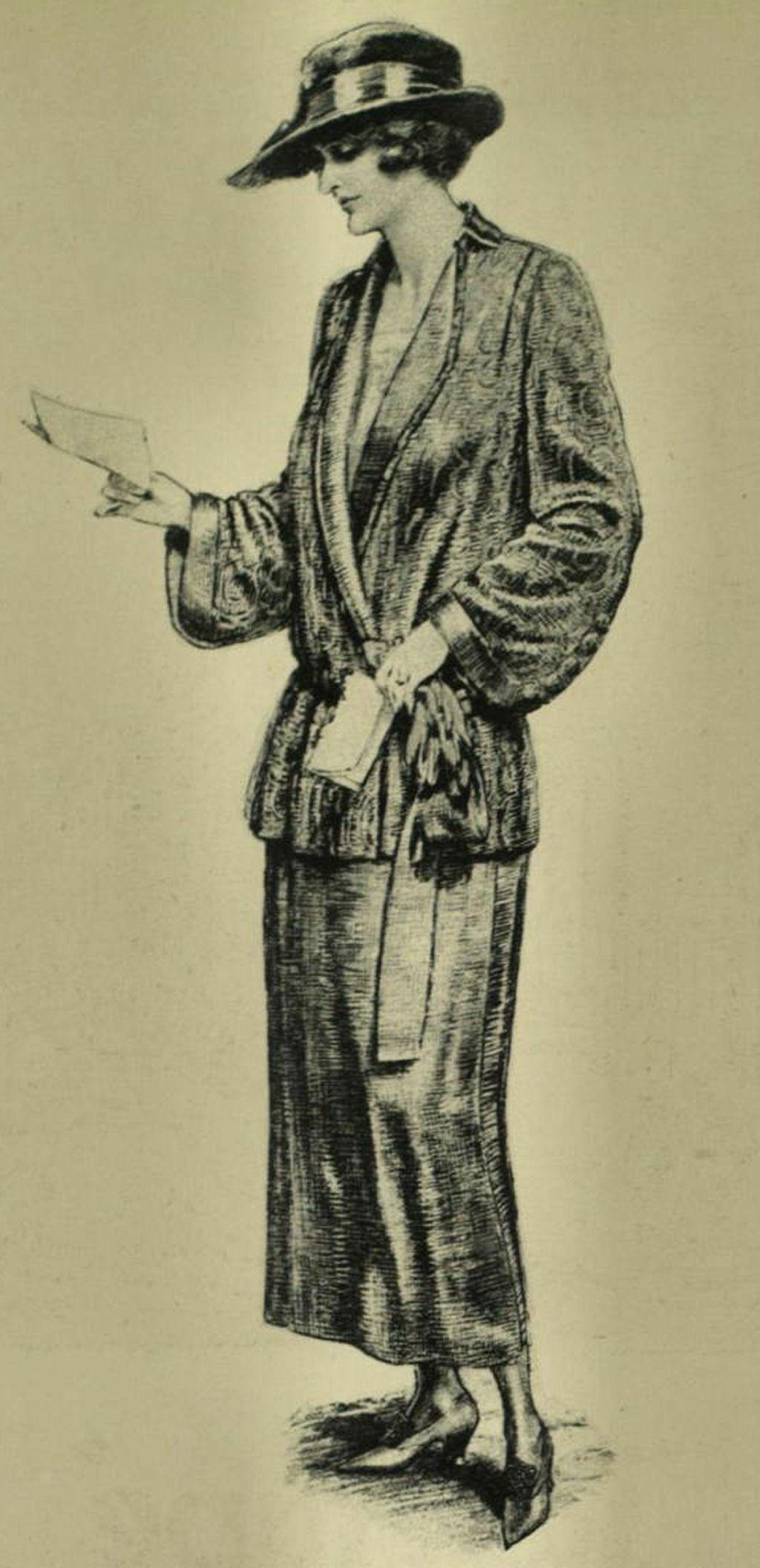

He wasted no time in enthusiastically explaining what lay behind his unusual advertisement. Ushering Miss Marks into the front room, he told her that he was setting up a musical academy in nearby Little Marlow. He explained that he had invented a new way of learning and teaching music and if she studied his system hard for two weeks she could then advertise it and take on her own pupils. He wanted to recruit around seven or eight young ladies to be his pupils at the new academy so they could become proficient enough to spread his remarkable invention of a new musical notation to others. This would revolutionize the teaching of music, he claimed, as his system did not use sharps or flats and was written in one key.

He wasted no time in enthusiastically explaining what lay behind his unusual advertisement. Ushering Miss Marks into the front room, he told her that he was setting up a musical academy in nearby Little Marlow. He explained that he had invented a new way of learning and teaching music and if she studied his system hard for two weeks she could then advertise it and take on her own pupils. He wanted to recruit around seven or eight young ladies to be his pupils at the new academy so they could become proficient enough to spread his remarkable invention of a new musical notation to others. This would revolutionize the teaching of music, he claimed, as his system did not use sharps or flats and was written in one key.

At 7pm sharp, Lilian Marks knocked on the door of Barn Cottage. George Bailey greeted her and showed her into the dining room. He explained that while she had been out, two more pupils had arrived from Scotland and being very tired after their long journey, had gone to bed. In fact there should have been a third pupil arriving but for some reason she had not done so. Anyway, tuition would begin the next morning and now there would be five pupils, possibly six if the missing lady turned up. The academy was taking shape.

At 7pm sharp, Lilian Marks knocked on the door of Barn Cottage. George Bailey greeted her and showed her into the dining room. He explained that while she had been out, two more pupils had arrived from Scotland and being very tired after their long journey, had gone to bed. In fact there should have been a third pupil arriving but for some reason she had not done so. Anyway, tuition would begin the next morning and now there would be five pupils, possibly six if the missing lady turned up. The academy was taking shape.

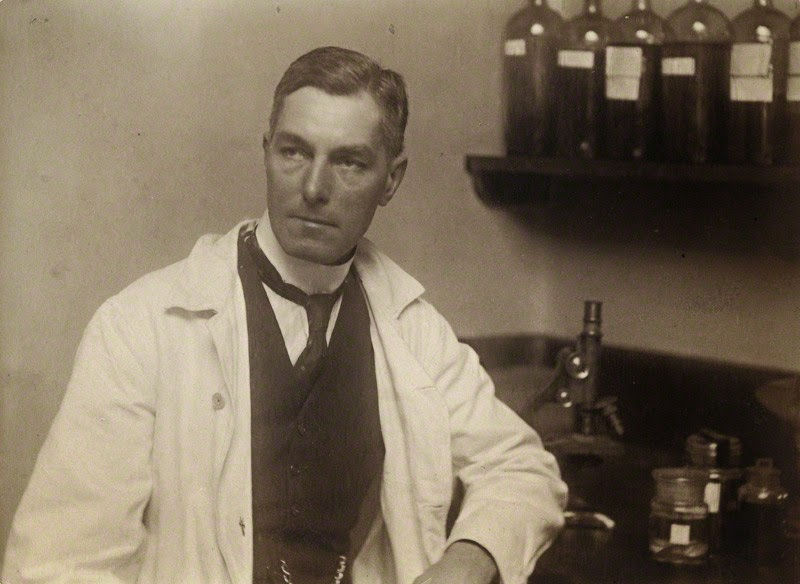

As a result of the inquest discovering Mrs. Bailey had been poisoned by prussic acid in her tea, and now the revelation that Mr. Bailey attempted to rape Miss Lilian Marks at that same house having seemingly murdered his wife there, the newspapers were becoming more and more incredulous as this bizarre and tragic story unfolded. Here is the Nottingham Evening Post for October 28th 1920, page 4

As a result of the inquest discovering Mrs. Bailey had been poisoned by prussic acid in her tea, and now the revelation that Mr. Bailey attempted to rape Miss Lilian Marks at that same house having seemingly murdered his wife there, the newspapers were becoming more and more incredulous as this bizarre and tragic story unfolded. Here is the Nottingham Evening Post for October 28th 1920, page 4

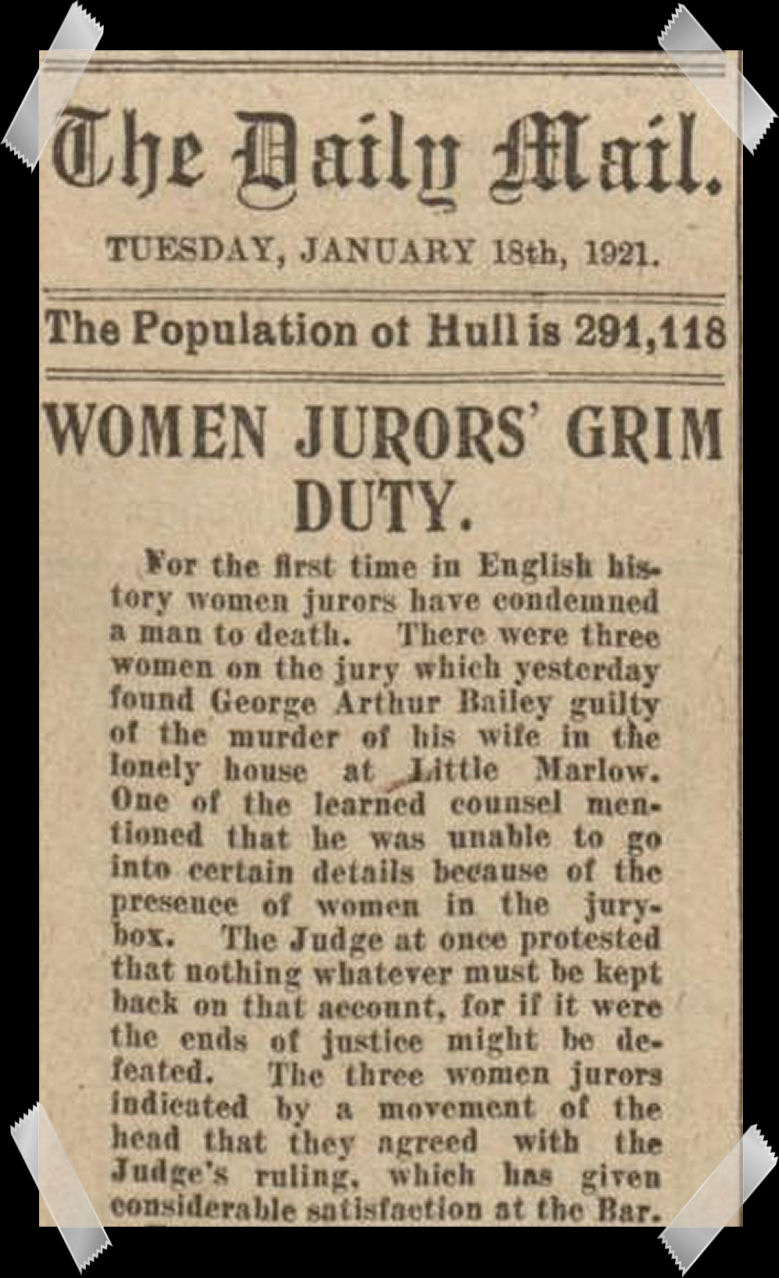

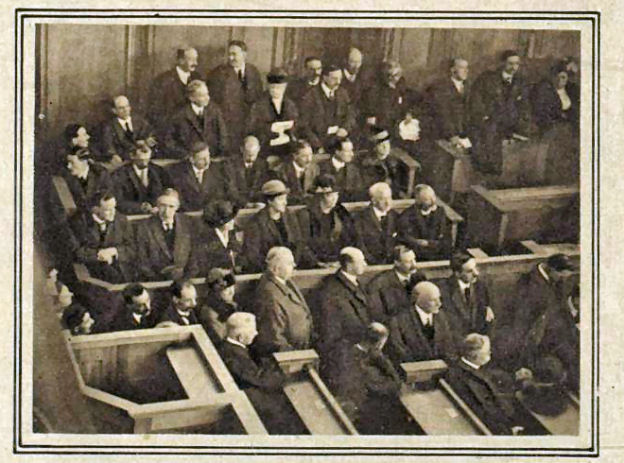

Source: Daily Mail January 18th, 1821 p.4

Source: Daily Mail January 18th, 1821 p.4

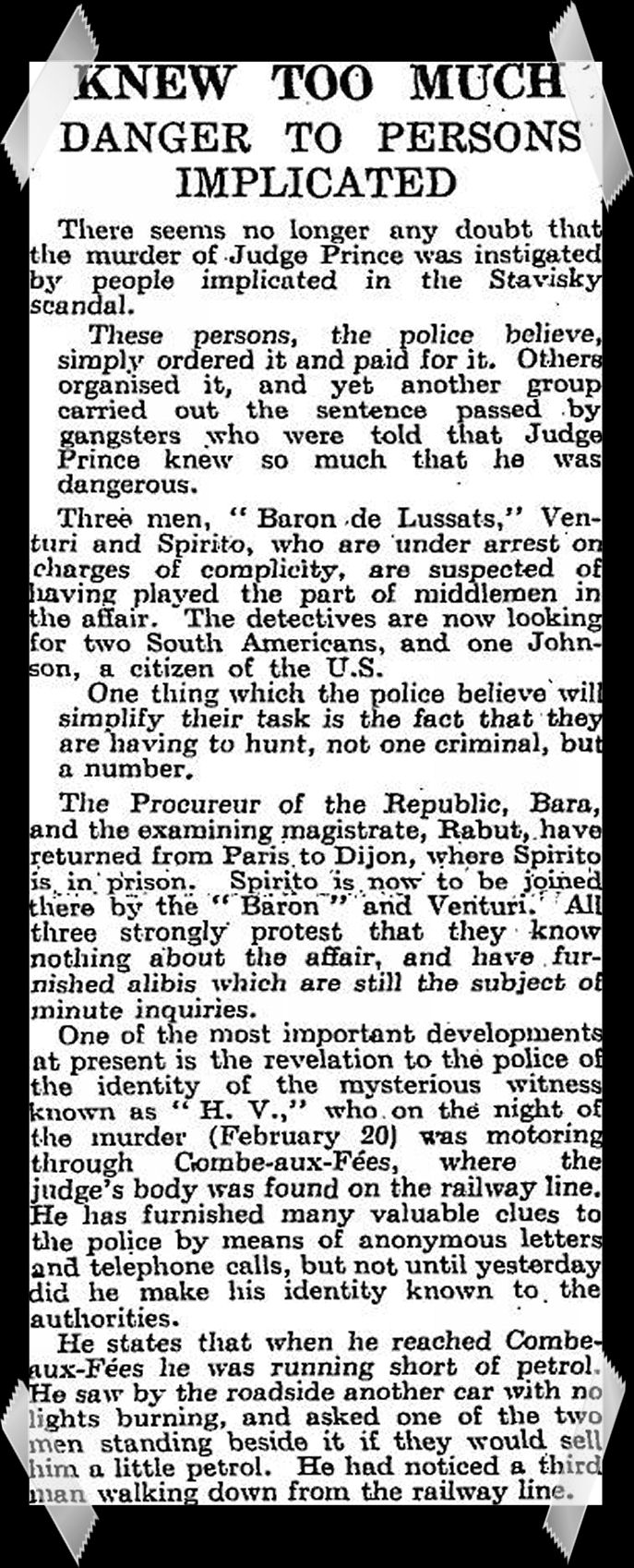

Also – here is a brief extract from a very competent précis of the whole set-up to start you on your own journey if you wish to take it: “A colossal swindle perpetrated by Serge Alexandre Stavisky brought scandal and ruin down on the heads of some of France’s most esteemed government leaders in the years preceding the outbreak of World War II. L’affaire Stavisky filled reams of official court transcripts as prosecutors attempted to sift through conflicting evidence to learn how it was possible for a Russian-born swindler operating out of a government-supervised pawn shop to cause so much chaos in the marketplace. As the court pondered, hordes of angry citizens standing outside the Chamber of Deputies chanted, “Assassins! Thieves! Staviskys!” A new word had entered the French lexicon of popular slang.”

Also – here is a brief extract from a very competent précis of the whole set-up to start you on your own journey if you wish to take it: “A colossal swindle perpetrated by Serge Alexandre Stavisky brought scandal and ruin down on the heads of some of France’s most esteemed government leaders in the years preceding the outbreak of World War II. L’affaire Stavisky filled reams of official court transcripts as prosecutors attempted to sift through conflicting evidence to learn how it was possible for a Russian-born swindler operating out of a government-supervised pawn shop to cause so much chaos in the marketplace. As the court pondered, hordes of angry citizens standing outside the Chamber of Deputies chanted, “Assassins! Thieves! Staviskys!” A new word had entered the French lexicon of popular slang.”

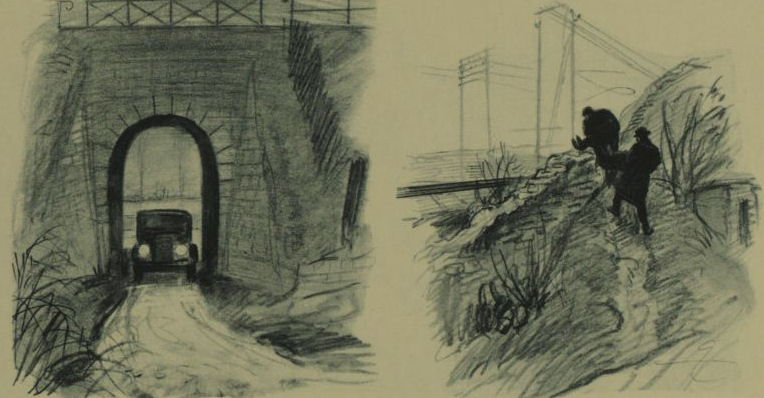

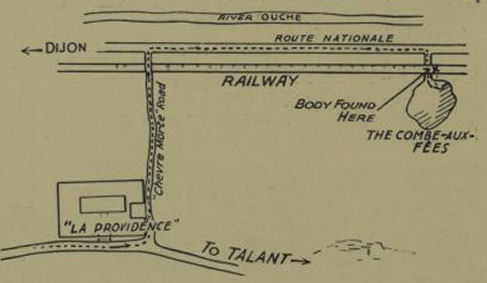

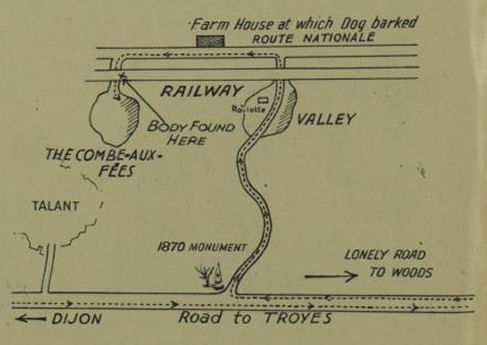

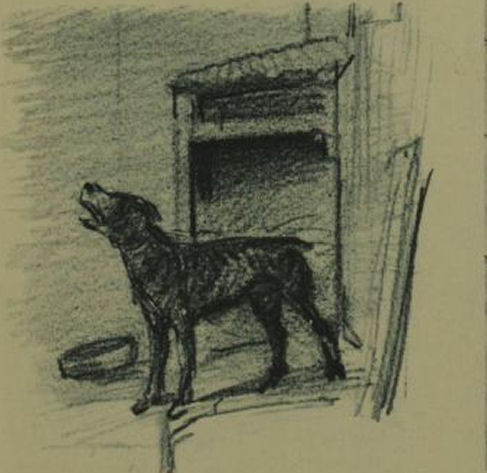

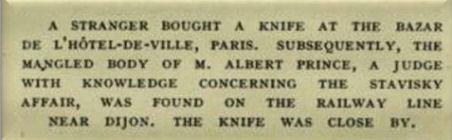

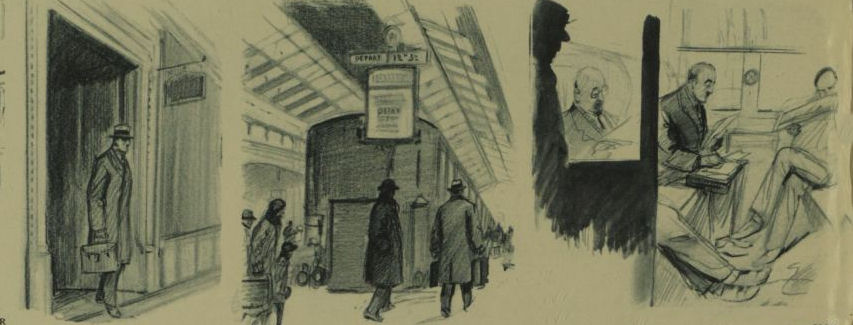

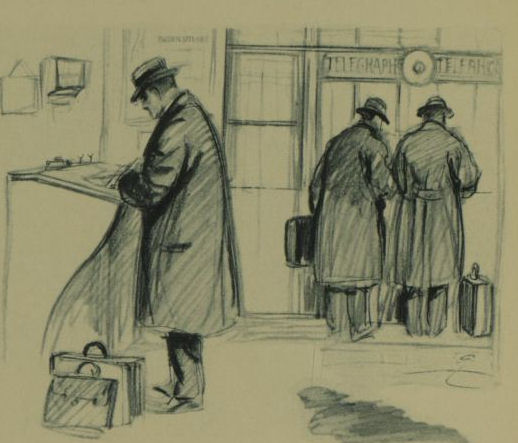

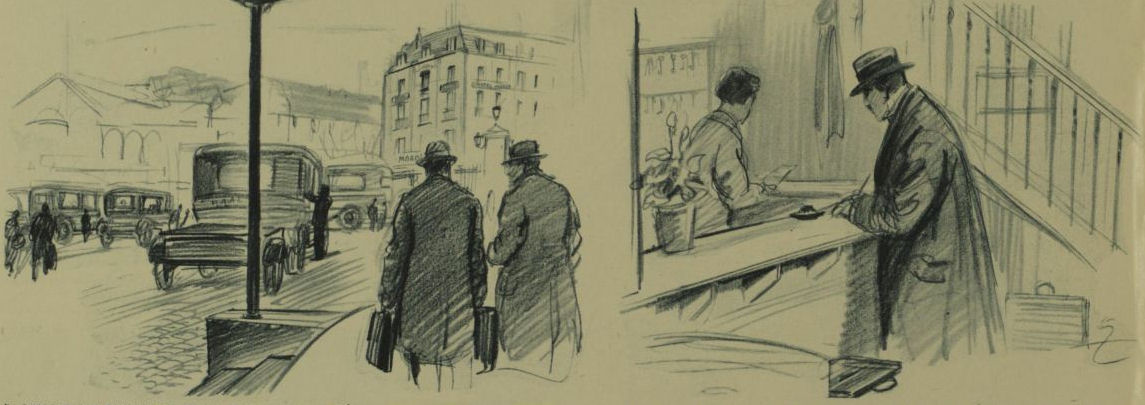

On February 20th, 1934, Albert Prince left Paris for Dijon, summoned to his mother’s bedside by an authoritative telephone call. At the Gare De Lyon, Monsieur Prince caught the 12.32 pm train for Dijon. Was he being shadowed? An important witness has stated that he was. During the journey from Paris to Dijon, Mr. Prince it may be assumed dealt with notes and documents carried in his portfolio – possibly, indeed with material concerning ‘The Stavisky Affair’. Was he spied upon in the train?

On February 20th, 1934, Albert Prince left Paris for Dijon, summoned to his mother’s bedside by an authoritative telephone call. At the Gare De Lyon, Monsieur Prince caught the 12.32 pm train for Dijon. Was he being shadowed? An important witness has stated that he was. During the journey from Paris to Dijon, Mr. Prince it may be assumed dealt with notes and documents carried in his portfolio – possibly, indeed with material concerning ‘The Stavisky Affair’. Was he spied upon in the train?

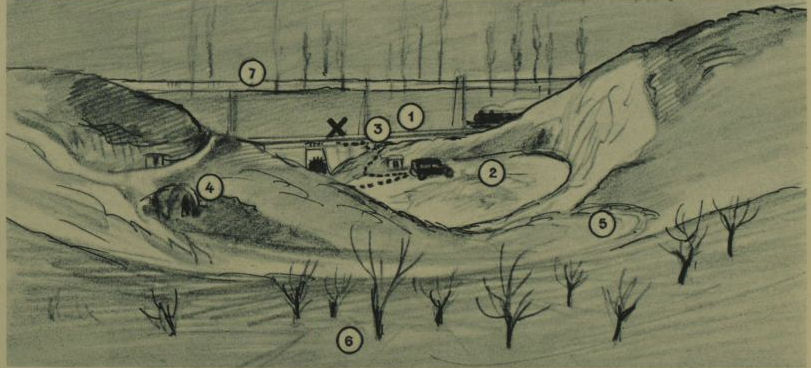

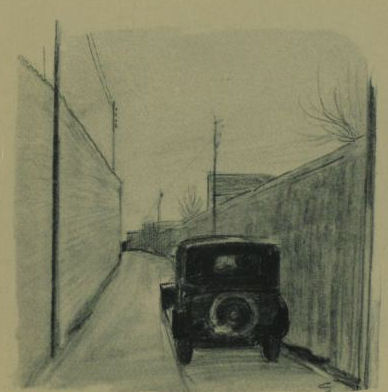

Here theory begins: Mr. Prince allowed himself to be driven into the country in the belief that he was going to “La Providence” to which he had been told his mother had been removed. Its wall is on the left.

Here theory begins: Mr. Prince allowed himself to be driven into the country in the belief that he was going to “La Providence” to which he had been told his mother had been removed. Its wall is on the left.