I am not always sure that I am on safe ethical or moral ground to refer to certain forms of fraudulent behavior as being ingenious. Nowadays, the very technology I am using for this blog is frighteningly adaptable to such nefarious use, leaving tens of thousands of innocent victims in its wake.

I am not always sure that I am on safe ethical or moral ground to refer to certain forms of fraudulent behavior as being ingenious. Nowadays, the very technology I am using for this blog is frighteningly adaptable to such nefarious use, leaving tens of thousands of innocent victims in its wake.

I’ve even heard the expression of such technology being ‘re-purposed’ as if innocently re-cycling it for the common good, which for the fraudster community is certainly the case until (or if ever) caught.

Historically, however, the print-media loved an ‘ingenious fraud,’ and had no difficulties in appraising the qualities of its ingenuity.

Here is The Times newspaper headline from Tuesday September 27th, one hundred and ninety-two years ago in 1825.

The Times (London, England), Tuesday, Sep 27, 1825; pg. 2;

So, ‘ingenious fraud’ number one is as old as the hills but I did not immediately spot the correct ending for poor Mrs. Bellow. Anyway this story gives me a good excuse to post a picture of the wonderful Catherine Wheel Inn in Southwark , sadly I have no image of the landlady but I suspect you have conjured one up in your mind’s eye.

Catherine Wheel Inn Southwark, London

It was a Saturday evening, September 24th, 1825, around 6.30pm, when a respectable looking man came bustling into the busy public house anxious to see the landlady who he appeared to know by name. Indeed, as soon as he saw her he came rushing over in a great hurry to speak to her as she sat by the bar.

“How do you do, Mrs. Bellow?” he said in a very familiar manner. “I have just come up from the country and intend remaining in your house until my business is arranged in town.”

Mrs. Bellow could not place him but his manner was so earnest, she assumed he had been a customer before, as many business people from the countryside stay at her inn and she cannot recall all of them. She thanked him for choosing the Catherine Wheel for his stay.

The gentleman then said, “Let a bed be prepared for me tonight, and Mrs. Bellow, I am anxious to be present at the opening of my favourite theatre, Drury Lane, and as I observe by the newspapers, there are a great many pick-pockets about, I shall leave my gold watch in your care.”

“Very well sir,” said Mrs. Bellow, “it will be safer here than in the theatre,”

The gentleman then drew from his waistcoat fob-pocket a splendid-looking engine-turned gold watch, chain and seals and desired that the utmost care was taken of it.

Mrs. Bellow, in order to let him see how careful she was of the property of others entrusted to her charge, immediately deposited the watch etc. in a bureau in his presence, which she observed was as safe as the Bank of England.

The country gentleman, much obliged to Mrs. Bellow, then left the Inn.

In a matter of moments he returned to the bar, saying, “Mrs. Bellow, I have not gold enough about me, and as the bank is closed now would you be so kind as to let me have three sovereigns until tomorrow?”

Mrs. Bellow did not hesitate to advance the sum, nor would she had been if he had asked for double the number of sovereigns, realising that the watch locked up in her bureau was sufficient security against a loss of between seventy to eighty guineas at least.

He then left and has never been near the Catherine Wheel again.

Mrs. Bellow thought it extraordinary that the owner of such a valuable watch would not have arranged to collect it, even if he was indisposed himself. She asked a jeweller she knew if he would call by to value it.

“Mrs. Bellow, you have been completely humbugged,” he said. “This fine-looking watch with its chain and seals is not worth ten shillings.”

She was very shocked and called to the police station at Union Hall who were very familiar with this ‘country-gentleman’s’ scam. They explained that this watch was indeed a very fine-looking watch with the appearance of being made of gold and an expensively engine-turned case that matches those high quality pocket watches. They are not sure how he obtains such a skillful replicas, but apart from its appearance, there is no more to it – no innards at all.

Once more the police issued a description of the man to all taverns and inns but he was never caught. Forty years of age, five feet ten inches tall, fair complexion, and red whiskers. He favours a blue-frock coat, a coloured waistcoat and light kerseymere trousers – so be warned.

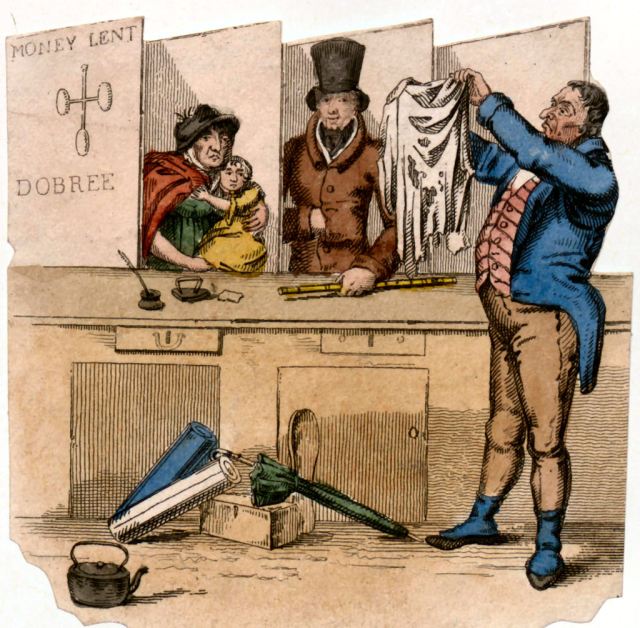

Ingenious fraud number two involved a woman described by The Times newspaper as, “a simple-looking young female named Elizabeth Davis.” Well this seems a contradiction given they then reported how she practiced “a most ingenious fraud on several pawnbrokers.”

[The Times (London, England), Thursday, Jun 18, 1829; pg. 3]

It was pawnbroker Samuel Sheppy who marched her to the police station and explained to the officers what had occurred. On Tuesday June 16th around ten o’clock in the morning, Elizabeth Davis had called into his shop to pledge two silk handkerchiefs for which she was given three shillings. Now three shillings at this time was a goodly sum of money as silk handkerchiefs were valuable commodities and three shillings was enough money for a couple of weeks rent for a furnished room for example.

Elizabeth Davis returned that same evening to redeem her handkerchiefs, but not with three shillings in cash, but with a shawl she wished to pledge instead and take the handkerchiefs back. Mr. Sheppy said the shawl was only worth a shilling or so which meant he could not make the exchange she requested. So reluctantly, the woman left the shop taking her shawl with her and having to leave the handkerchiefs as security until she found the money to buy them back.

Fortunately for Mr. Sheppy, when he put the newspaper-wrapped handkerchiefs back into storage, he noticed it did not feel quite right and on checking discovered it was a cluster of old rags instead. He chased after Elizabeth Davis and confronted her with this theft, taking her to Bow Street station.

The police then debated whether she should be charged with stealing the handkerchiefs or the money which she had been given to her for pledging the handkerchiefs. They had experience of this quandary before and rather than proceed at court level, it seems judges were inclined to acquit the offender with a stern warning.

However it was known by one officer that several pawnbrokers had recently been duped in this exact manner, so with other pawnbrokers able to produce similar bundles of rags for exactly the same two handkerchiefs pledged by Elizabeth Davis, they could proceed to charge her with fraud.

Thomas Race from Townsend and Page Pawnbrokers in Little-Russell Street gave evidence that he had been offered these same two parcelled -up handkerchiefs for which she demanded four shillings, but he only offered her three shillings and sixpence. She was not prepared to accept that and took her parcel back as he went to serve another customer. She then quickly changed her mind, pushed the parcel over to his side of the counter and he parted with three shillings and sixpence for what turned out to be a parcel of dirty old rags.

The final part to Elizabeth’s plan had been to sell the tickets to others who had very little money to part with but she sold the tickets for around sixpence so they could make a profit by redeeming the ‘handkerchiefs’ to re-pawn elsewhere or sell. As she reminded these other victims she befriended with her generous offer, if the pawnbroker gave her three shillings and sixpence, they’ve got be worth at least four or five shillings which would be his profit. So, in several cases, the pawnbroker concerned did not know about the switch until an ‘innocent’ pawn ticket purchaser came for their bargain deal sold to them by Elizabeth.

Now, when I began this blog. I briefly mentioned that nowadays with the internet we have increased the scope for fraudulent activity many times over. It’s impossible to calculate.

Interestingly, however, little has changed when it comes to the familiar scam emails that use some tale of woe to try and elicit some funds for a good cause where someone claims to have fallen on hard times or needs modest assistance in some way to escape a dire situation. Please send money to etc. etc.

A well-known, kind and sympathetic reverent, William Weldon Champneys, was a very active community man in his parish of Whitechapel where he was responsible, as he put it – “For 34,000 souls.” He soon discovered he was not alone in London when he received a very heart-rending letter asking for assistance.

The letter he received was from America with a Philadelphia postmark recounting a distressful situation encountered by one Fanny M. Jackson and her need for money to save the family from ruin. The actual story Fanny relates in this letter received by the Rev. Champneys is, unfortunately, not known but if you are reading this blog then you will know exactly the kind of letters your spam box collects – so just re-jig to fit the surprise value of receiving a distraught ‘disguised’ begging letter nearly one hundred and fifty years ago in 1869 – from America – arriving through the letter-box of a kindly vicar in the east end of London, with a cleverly planted inducement to do more. i.e. the misdirected letter lure, which he (nearly) fell for as you’ll see below.

Champneys wrote to The Times newspaper. I’ve reproduced his letter in full. Please be patient with it and you will see how nothing is new when it comes to this chestnut of a scam.

The Times (London, England), Saturday, May 08, 1869; pg. 12;

Church & Chapel Good Saviors

I began this blog by wondering about whether calling certain frauds ingenious might be morally suspect. I would like to leave you with one that seems – given Mr (or rather Herr) Bartholl’s background – less of a fraud and more of a celebration.

The Times (London, England), Saturday, Aug 11, 1934;

Bon Appétit